This is the fourth and final research note from Epsita Halder, one of the researchers who received the Social Media Research grant for 2016.

I took a murky turn between the Sunday market on Biplabi Rash Behari Bose Road and the Portuguese Church that is called the Portuguese Church Lane. Behind the white church, in the lane teeming with resting pushcarts, small shops and old shabby buildings, I found my address – 10, Portuguese Church Lane, Kolkata 700001. It was a typically dilapidated building whose façade could not be fully seen from where I stood, it overwhelmed my field of vision. There was an A3 sticker on a closed part of the door that spoke about martyrdom and I was sure that it was the front gate of Haji Kerbalai Imambara. Men stopped and looked askance seeing me enter the gate, three followed me in. It was a typical building from colonial times – a rectangular courtyard in the middle and a sprawling three-storey building around the courtyard with balconies as frills of first-floor rooms. The courtyard was empty and a melancholic iron pole with black and green flags tied on top stood with the sacred panjatan pak rising to the sky. I could hear pigeons grumble loudly, and as I took a step forward, some darted about a little, reluctant to allow me in. The two men and a boy who had followed me, watched me with uneasy curiosity as I clicked pictures of the green sacred flags. They did not know what to make of me. Never had I visited such a deserted imambara either. It didn’t look like anybody took care of the sacred space. A signage distinguished one grilled and locked door on the ground floor from similar ones. On it was printed the name, Haji Karbali Imambara. Other rooms on the ground floor were occupied by tenants, their nameplates showing the usual, endearing pan-Indian jumble. The grille that fenced the balcony had HK in caps. This must be Haji Kerbalai for HK, but that seemed a bit tautological, I felt self-congratulatory at becoming an overeager detective but was surprised with this overemphasis of identity.

Could you please tell me when they come for the mourning session? I asked the men calmly, casually hiding the eagerness in my voice. But the older man, visibly uncomfortable, started leaving the courtyard asking the boy to follow him. When they feel like, the boy answered with extreme reluctance and turned to join the other two who hadn’t entirely left, but were watching me from outside the gates.

I wanted to climb the dark and broad wooden staircase leading to the upper storey, but didn’t know if I should. I stood undecided under a row of sooty meter boxes. A short man, looking annoyed, came down and asked me, not very politely, about the photographs I’d clicked. I showed him on the viewfinder the semi-dark steps, the pigeons and the panjatan pak. With whose permission have you clicked them? I fumbled for a reply as I’d never encountered this tone of suspicion during my regular visits to imambaras these past six-seven years. I managed to ask if I could go upstairs and learnt that it could not happen without the permission of those staying upstairs. Who are they, I asked. Those who are supposed to stay there, declared the man, and with such gruff metaphysics, disappeared. I called up Nizam Haider, a member of the trustee I had been in contact with but who unfortunately had gone to Metiabruz[1], another predominantly Shia locality in Kolkata, that afternoon. Puzzled and heartbroken, I decided to pack up.

Suddenly, the suspicious man came back and asked me to come upstairs. Taken aback, I accompanied him to a balcony redolent with pigeon droppings where two men were ready to welcome me. Yes, Nizam Haider, whose cell number I got from the website www.imamproperty.com, had called them from Metiabruz. I sat at the imambara office with manager Muhammad Ali and his young nephew Abu Baqr and talked about the imambara. This was an imambara established sometime not after mid-19th century and they added as I read on the website, had been occupied by intruders in due course. A physical struggle took place between the illegal occupants and the community on July 13, 1997, and a long legal battle followed.

Imambara (from www.imamproperty.com)

Imambara (from www.imamproperty.com)

I took out my papers, downloaded and printed from website www.imamproperty.com where I came to know about this imambara from and started discussing the issues mentioned there. Utterly surprised with my homework, the uncle-nephew duo reaffirmed the history published on the website. They had not checked the website themselves. Muhammad Ali was not into much virtual networking, but the nephew Abu Googled the date when this imambara was founded and my name on his cell phone. It was in 2011, they confirmed the date given on the website, when the trustee took over the keys from the emissary of the court.

Since then, the trustee board took care of maintaining the material and moral status of the imambara. Yes, the website has legal papers from the case, the hearing, to posit its claim to the virtual public.

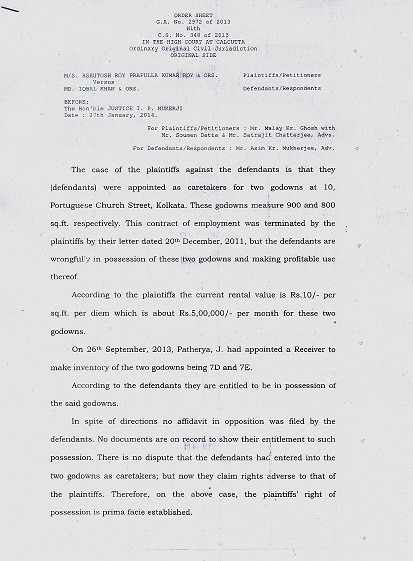

Legal papers (from www.imamproperty.com)

Legal papers (from www.imamproperty.com)

Muhammad Ali fixing the tubelight

Muhammad Ali fixing the tubelight

Muhammad Ali’s phone was ringing an elegy – “Haye Husayn Haye Husayn”- which he gave me via Bluetooth and showed me books and journals published by the other imambaras. Then he brought a bunch of keys and by opening up a flurry of doors one after another took me to the magnificent hall where the mimbar (the prayer stool) and alam (flags) were kept under heavy glass chandeliers. Big mirrors with fish and lion symbols were telling me the possible story of a Lucknow link, a derivative of the Iranian passion itself. I was dumbfounded to see such a magnificent mourning hall and corridors inside that shabby and melancholic building. This is second to only the Metiabruz royal one, involuntarily I exclaimed, which made Muhammad Ali gloat in happy pride. But when and how did all these begin? Who was Haji Aga Khan? When did this Urdu-speaking community flourish and start commemorating Muharram in Kolkata? What propelled them to publish online material, not about the ritual but real estate?

Actually no sooner had I settled down inside the imambara office that I could sense the reason for the online claim and the offline anxiety and suspicion. The initial mistrust towards me was an offshoot of the history of this imambara which has to be reclaimed from trespassers and forced occupants. The website needs to publish the necessary document to affirm its legal claim over property in public, as it has always been suffering the insecurity of losing its sacredness. The layout of the website, where a whole array of the imambara sites is reclaimed and categorized, offers more than virtual religion and online devotion and creates an archive of tangible belongingness which marks and settles the community online.

My study in this point chooses the parameters of ‘religion online’ (information about religion without interaction) over ‘online religion’ (interactive mode of participation in ritual) when I start analyzing www.imamproperty.com as a one-way archive of religious knowledge without the scheme of interaction[2]. I was thinking that perhaps adopting the structure of ‘religion online’ was necessary for a website that is the ‘official’ archive of all legal papers and new policies through which their claim over their sacred land could be affirmed. This religion online not only configures the Shia religious community, but also forms other versions of the community by remaining conceptually open to any public arena with the specific strength of legal papers as the connecting link between the community insiders and outsiders. But my further enquiry via the other links embedded in the primary website opened new windows, breaking my earlier concept of an official platform of ‘religion online’. The website of Waqf Management System of India opened (www.wamsi.nic.in) claiming its status as ‘an on-line system for searching Waqf Properties in your area & their status’ with an embedded feedback system. “Public Interface of WAMSI On-line System” was claimed to be launched to get help from the common people “in building a correct and up to date inventory of Waqf Properties by sending DATA Verify Form”.

It is more than real estate of religion, it is an exclusive platform to disseminate knowledge to the community and link it virtually, the embedded links, like the bricks of the imambara, carrying many surprises. For many people of the community who are neither Internet-savvy nor comfortable with English, such websites stay out of bounds. Muhammad Ali assured me that even if he could not say anything about the website and other things, he would definitely arrange a meeting where trustee members would be present to give me information. We need to see whether this offline asymmetry in knowledge distribution affects the promised ‘many-to-many’ kind of virtually networked form of non-hierarchical knowledge. A study of Shia websites seems a very important chapter in the study of the interface between religion and new media.

Notes:

[1] Metiabruz is situated in the Southern fringe of Kolkata where Nawab Wajid Ali Shah took refuge when he was exiled by the British in 1856. The Nawab attempted to build a replica of Lucknow in Metiabruz where with the emergence of Awadhi architecture and culture, the Shia morning ritual started to flourish centering on the royal imambara. Shia people in Kolkata and nearby districts make a point to visit Metiabruz occasionally to strengthen community bond.

[2] Christopher Helland differentiates between ‘religion online’ and ‘online religion’ basing his exercise on the Christian religious websites in the beginning of his theorization of religion on the internet. The binary opposition between ‘religion online’ which stands for unilateral archivization of religious information , and ‘online religion’ which provides interactive and participatory modes for the internet user, was conceived by looking at the attributes of the official institutional and non-official informal ones functional in the late 90s. In Helland’s early theorization, information without interaction, was the basic criteria of official religious websites, whereas the unofficial ones stood for interaction and participation. He expands his primary theorization by emphasizing on the possibility of a ‘spectrum’ between the poles of ‘information’ and ‘interaction’ and marks various degrees of the possibility of interaction. Christopher Helland, “Online Religion as Lived Religion: Methodological Issues In the Study Of Religious Participation on the Internet”, Online – Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 1.1 (2005)