In this post, Ankush Bhuyan, one of the researchers who received the Social Media Research grant for 2016, introduces his proposed work.

The demand for Bodoland, a separate state from Assam, has garnered national attention in the last few decades because of the violence and insurgency that has ensued in its wake. In recent times, the Bodo agitation has become an important component in the political discourse of Assam, and remains a complex and emotive issue.[1] There has been considerable focus within the Bodo community on this issue that is linked with questions of identity, culture and language. Additionally in the last two decades, there has been an emergence of locally made low-budget productions due to the availability of affordable digital technology. These are made in the various languages of the North-eastern region, apart from Bodo, and they are loosely known as VCD films and (music) videos.[2] The Bodo VCD films and videos circulate mostly within Bodo populated areas of lower Assam and travel to bigger cities like Guwahati through non-mainstream channels; usually sold directly in the form of compact discs in local markets with little to no promotion and official release.

Alongside this the Internet continues to spread to the remotest parts of the region providing access to people to a wide variety of material from films, music videos, songs, images, news, etc., which are also shared through websites like Facebook and YouTube. The (new and old) material shared leaves a trace in this virtual space where ‘imaginary communities’ interact and come together. This enables the journey of this interaction in the digital world to be mapped for it to be studied. This project aims to capture the current moment where social media intersects with VCD films and music videos, in their entirety or in the form of clips available online, and questions of Bodo identity. What is it to be Bodo? How does social media play a role in the formation and the consolidation of identities? Can the use of technology and aesthetics in the VCD films and music videos provide some insight on the above questions? Through this study I hope to shed some light on the use of social media that may link to larger questions from the region regarding identity, culture and circulation of mediatised images within a political movement.

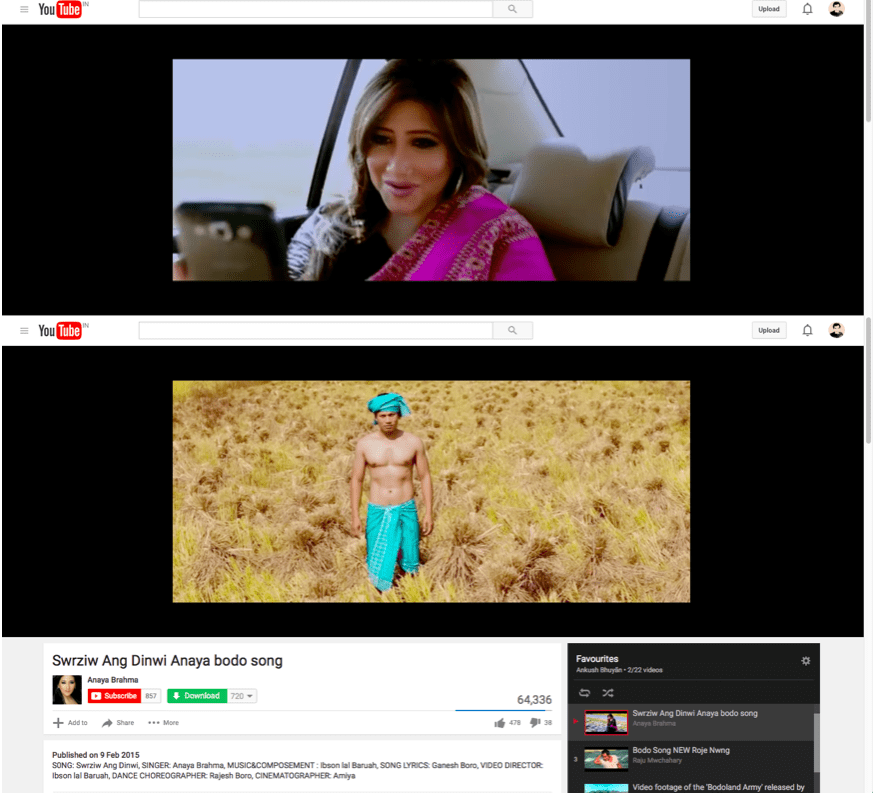

Two screenshots of a music video by Anayan Brahma. This music video evokes her Bodo identity through the landscape, ethnic wear and the language apart from the title. See Anaya Brahma , “Swiziw Ang Dinwi Anaya bodo Song”. Online Video Clip. You Tube. You Tube, 9 Feb .2015.05 July 2015

Scholarship on media, circulation and film cultures in the Northeast has been slowly gaining momentum over the last decades. Anirban Baishya’s work on Assamese cinema is one such example where he traces the industry’s evolution to the present day.[3] He locates Assamese cinema in the larger socio-political history of the state, of an Assamese identity, as he writes that, “the history of cinema, or any other history for that matter, cannot be divorced from moments of change and disjuncture that change the spectrum of relations in a given social, political and economic setting” (1). In another section, Baishya writes that:

As a relatively recent technological innovation the VCD has revolutionised the ways in which we have come to receive and even study films in the contemporary… Further, the advent of the VCD film also spawned productions in Assam’s various languages…However, in opposition to the paucity of material…my interrogation of the ‘VCD film’ phenomenon was thwarted by exactly the opposite—overproduction. (164)

Neikolie Kuotsu’s work on the Korean Wave in the North-east has highlighted the complex circulation of popular Korean films and tele-serials in the region that focus on the way piracy contributes to cultural reproduction, dissemination and reception while negotiating questions of identity, citizenship and nationhood in this region.[4] In addition, Ravi Sundaram’s work focussing on piracy in urban centres may be useful to understand the ways in which piracy gives rise to a recycled modernity,[5] that is not concerned with modernity’s search for originality, but linked to the moment of globalisation,[6] circulation, and the trace it leaves. Even though Sundaram’s work is based on an urban centre’s piracy, it is a useful approach for this project which aims to looks at online circulation, questions of piracy and legality.

There are numerous studies by scholars like Brian Larkin, Lotte Hoek, Lawrence Liang, Sudhir Mahadevan and others that have highlighted the non-mainstream and extra-legal forms of exhibition, media infrastructures and circulation. However, there is a lack of study of online interactive spaces from the North-east which contribute to and form another aspect of similar discourses. This study attempts to close that lacuna by studying the afterlife of VCD films and music videos online, and to critically engage with nonlinear media assemblages that make communities come to life,[7] while leaving a possible trace and spillage in non-virtual spaces.

The Bodo videos that are online, like on YouTube, are able to invoke the Bodo identity through the language, the bodies, landscape, clothes, etc., and through the title of the videos and the numerous comments that are posted. Here the peoples and communities who feel neglected and have been sidelined by the state and by more mainstream sections have a space.[8] The major chunk of Bodo VCD films are slapstick comedies, melodramas and a small number deal with the socio-political issues of the region.[9] A successful Bodo VCD film called Hainamuli has had five parts and this series humorously deals with various issues such as vote bank politics, superstition, etc.

Anirban Baishya mentions in his dissertation that ‘legit’ filmmakers, like Manju Borah, consider VCD films as cheap copies of Bollywood films. The circulation and production of VCD films and music videos has created an economy within a region for a certain kind of product and aesthetics. The bootleg aesthetics,[10] and the low budget of such films, has helped them to survive the onslaught of mainstream and big budget films, and moreover, they find an afterlife on websites like YouTube from where they are shared and reposted on other social networking websites for them to continue to circulate. Online media is becoming increasingly important from an ancillary space as local artists/actors/singers can circulate and advertise their work to gain currency and, for example, to be able to perform in live shows. This dynamic and evolving mediascape of intersecting networks falls under the rubric of my project.

To put this in context, Ravi Vasudevan in his work has also focused on the emergence of new media networks which seems to be in direct competition with legitimate markets.[11] Vasudevan highlights how these transformations have complicated the notion of public spaces, particularly the Habermasian discourse on the public that apparently “capture[s] the full dynamics” (412), whereas according to Vasudevan, something always slips through the cracks. He points to media driven by illegal copies and downloads as an example of the slippage through the cracks. He highlights instances in Mumbai, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Manipur that point to a developing digital production culture that are dependent on local resources and are circulated via VCDs. Vasudevan writes that such networks are not distinctive from larger film industries as there are examples of actors and technicians who move between local set-ups and the more lucrative film industry in Bombay.[12] He highlights on the grounds of these new transformations that there is an “emergence of a [new] legal video film culture…” (411). He finds the digital moment to reiterate this function of cinema through different modes, and it is part of a wider engagement that concerns the public sphere, film production, circulation and reception.

My study is located carefully between this relatively new phenomena of the VCD film and music video culture of a particular community within the state of Assam and its online presence. I hope this positioning would shed light on how we understand North-eastern film culture, use of technology and aesthetics, and furthers our interrogation of identity and conflict between the ‘dominant’ Assamese and Bodo language communities. This project would attempt to grasp the evolution and mutation of the use of social media websites like YouTube and Facebook, intersecting with the idea of online communities, by focusing on the Bodos.

Notes:

[1] For a perspective on the political situation in Bodoland, see Mochahari, Monjib. “Of Politics, Conflict and Reconciliation in Bodoland.” The Password: We Don’t Resize The Truth But Retell… The Password, 12 July. 2015. Web. 12 July. 2015. And the situation in the context of the upcoming election in April, 2016, see Bujarbaruah, Minakshi. “All You Need to Know About Bodoland Politics Ahead of This Year’s Assam Elections.” Youth Ki Awaaz: Mouthpiece for the Youth. Youth Ki Awaaz. 15 March. 2016. Web. 15 March. 2016.

[2] Please note that there are now instances of visually and technically better produced music videos, which indicates an effort to form a more organised system of production and marketing with a certain kind of aesthetics that is reminiscent of Bollywood music videos (for example, see fig. 1 for its production quality).

[3] See Baishya, Anirban. “Imagining Assamese Cinema: Genres, Themes and Regional Identity.” Diss. Jawaharlal Nehru University, 2013. Print.

[4] See Kuotsu, Neikolie. “Architectures of pirate film cultures: encounters with Korean Wave in “Northeast” India.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 14.4 (2013): 1-21. Web.

[5] See Sundaram, Ravi. Introduction. Pirate Modernity: Delhi’s Media Urbanism. By Sundaram. London, New York, New Delhi: Routledge, 2010. 1-27. Print.

[6] Arjun Appadurai writes that globalisation and transnational cultural flows has to be examined keeping in mind the contradictory ways in which these cosmopolitanisms work and do not adhere to established truths.There is a shift in the imagination in social life in the global cultural order through cinema, television and video technology. Images and ideas have taken a new force as more people see their lives through the possibilities offered by mass-media, which provides the possibility of imagined counterparts and communities to be formed. See Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: The Cultural Dimensions of Globalisation. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1996. Print.

[7] Amit Rai writing on the media assemblages attempts to shift the focus of audiovisual media from a representational form that produces a linear relationship to identity, to “a method of diagramming nonlinear processes of an assemblage” (3). Like Rai, I am also interested in is how in the new media assemblage identity and bodies are mutating through repetitions. See Rai, Amit. Introduction: India and the New Non Linear Media Assemblage. Untimely Bollywood: Globalization and India’s New Media Assemblage. By Rai. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009. 1-20. Print.

[8] Sanjib Baruah who has written extensively on the modern India State vis-a-vis the Northeast focuses on questions of citizenship that has manifested in the region through faulty institutions and problematic policies that do not take into account the ‘poetics of homeland’. Baruah’s theoretical framework to understand the situation in the Northeast helps in developing an understanding of the specific situation in Bodoland. See Baruah, Sanjib. Durable Disorder: Understanding the Politics of Northeast India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2005. Print.

[9] There has been only a few Bodo films till the coming of VCD films about 10-15 years ago. The first Bodo film is Aleyaron (1984) directed by Jwngdao Bodosa, a well-known Bodo filmmaker who has received regional and national recognition for his work.

[10] See Hilderbrand, Lucas. Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright. Durham: Duke UP, 2009. Print.

[11] See Vasudevan, Ravi. Conclusion and Afterword. The Melodramatic Public: Film Form and Spectatorship in Indian Cinema. Delhi: Permanent Black, 2010. 398-414.Print.

[12] Anaya Brahma (see fig. 1) has started singing in Hindi. See Crescendo Music / Productions. “Lagan Lagi – Anaya II Soft Hindi II.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 20 Nov. 2014. 05 July. 2015. And she has made headway into Bollywood, see The Bodo Tribe 18 (Team). “Anaya Brahma is new rising Bollywood singer cum actress all the way from Bodoland.” The Bodo Tribe ‘Online-Magazine’ . The Bodo Tribe Mag., n.d. Web. 05 July 2015.

[Last Updated on 19 April, 2016]