This is the fourth and final research note from Vibhushan Subba, one of the researchers who received the Social Media Research grant for 2016.

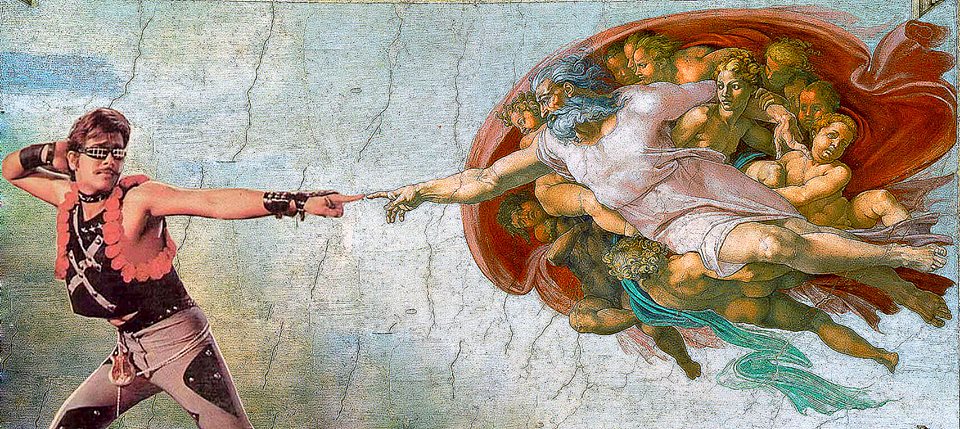

Credit: I love trashy hindi movies

Credit: I love trashy hindi movies

The more I explore the cinephiliac circuits of obscure small budget films manifesting itself through networks of social media, the more I am reminded of an old curiosity shop stuck in the corner of a street with all kinds of valuable junk. In this room, the gathered and the collected, the scattered and the discarded, in this room the past and the present, the lost and the found, in this room the dead and the undead. This work of collecting and preserving the past is marked by the increasing importance of the fragmentary (the clip, the tribute, the ephemera etc) where many different pieces fit together, like in a puzzle, where the ludicrous, the ugly, the obscene, the erotic and the horrifying come together to construct a universe of the obscure.

For, what else is a page like I like trashy hindi movies if not a curiosity corner of obscure small budget films. It is an eclectic collection of old film posters, trivia, information, production stills, magazine excerpts, clips, memes, gifs, stories, film ephemera and just about anything that deals with ‘trashy hindi movies’ as the title itself suggest. The description says it all, “If you love mindless, absurd, B grade, obscure, trashy, and all kinds of Hindi movies, then this is the group for you.” Sure, the definition of ‘trashy’ varies from member to member but the general idea is floated in the introductory section which reads, “One thing that is always asked is “what is a trashy movie?” Is it a flop, is it a sleazy movie, does it have to be horror? Well, Trashy for us is something that has become a cliche or is so bad that its really good. What it is not is something so boring that it interests no one.”

Excerpts of a personal interview with Keith Allison, writer and editor at Teleport City, a website of Cult and Obscure films, online since 1998 conducted June, 2016.

On the definition of trash, cultural detritus[1]

I’m not entirely certain i think of them as trash. I mean, Shakespeare was considered by many to be trash in his time. And many major studio productions are more easily classifiable as trash than many low-budget films. Fringe, low budget, outsider, even z-grade perhaps. But to give a definition of this particular type, they are films for me that are made independent of the major studios, with meager resources, starring either amateurs or a stable of obscure professionals (the same people pop up in so many z-grade Bollywood horror films that it’s hard to call them amateurs), dealing with topics and subject matter that are considered distasteful or taboo to the mainstream — and yet are often coveted and later mimicked by the same mainstream that dismissed or condemns them.

Credits: I love trashy hindi movies

Credits: I love trashy hindi movies

Cinephiliac desire of the weird and the obscure

I think that varies widely from person to person. For me, I grew up on a wide range of films back when television was much more limited in its distribution — just three channels, plus local public TV. Everything from old horror to Tarzan movies to Godzilla to Flash Gordon serials was bought cheap to fill the airwaves, so I never really developed a sense of “I watch movies only from this era” or only this type. And that craving for variety continues, especially now when so many movies look so similar. I’m a fan of most Marvel superhero movies, but I find they’re all pretty much the same — same beats, same stories, same colors, same effects. For someone who craves new things, you have to look elsewhere, and that almost always leads you into weirder, more obscure backwaters of cinema. I also enjoy being surprised. I enjoy finding new things. And I enjoy learning about the pop culture of countries other than my own. And yes, the kid in me still revels in the shock value these films can deliver. I’ve never been a big fan of the authoritarian or of the remote judge who feels the right to dictate morality. I freely admit, however childish it is, enjoying films that shock and annoy, even if my own tastes are rather reserved (for instance, I enjoyed gore as a teenager but have always been more interested in mood and atmosphere in horror — the stuff of the 20s and 30s more than the 70s and 80s). I enjoy spectacle as much as I enjoy small, brooding, personal films.

Perhaps there is the reason why “It is so bad that its good!” is a phrase that is bandied about quite often on the internet these days followed not too distantly by the ‘sleazy’, weirdest, shoddiest, the most obscure, the strangest that make up the better part of the vocabulary of the undead cinephiles in India. For years the small budget Hindi film (B-movie) travelled in the moffusil circuits drawing committed audiences. These were films made with extremely low budgets with no recognisable faces and completed in five to ten days. Kishan Shah claims that he has never taken more than five days to complete a film[2]. S.V. Srinivas (2003) locates the B circuit in non-metropolitan areas where the distributors pick up the cheapest films, the last laps of distribution where only small players operate. Caught in miniscule budgets these films have established their own logic of production, one characterised by an uncharacteristic operational mode where films find exhibition space in run down single-screen theatres, morning shows[3] and travelling and tent cinemas. Uncharacteristic, because it finds recourse in a deeply improvisational framework where spliced pornographic sequences, called bits or cut-pieces[4] often appear to attract audiences and to evade the censor board. This is but one example of the the informal trajectories that these films negotiate to reach it’s audience.

Credits: Hotspot film reviews (Da Khwar Lasme Spogmay (1997) AKA The Cat Beast)

Hotspot film reviews [Film review site from Pakistan that reviews Pashto Horror and small budget Hindi films amongst others]

The small budget film[5] though never reached the multiplexes and with the speedy folding of the single screen theatres following the entry of the multiplexes many feared that the days of these films had come to an end. However, as people speculated the future of small budget films and single screen theatres, fans and collectors started uploading films on YouTube, writing reviews and blogging about these films. As a result the audience constitution of these films have changed with changing formats and delivery platforms. The contributors to I love trashy hindi movies are students, copy writers, filmmakers, researchers, academics, engineers, financial analysts and such, an entirely different demographic group. A large number of women are members of this group who contribute regularly which is quite unlike the earlier following, dominated by men. The cinephiliac desire for obscure small budget films that erupted online in the early 2000s has opened it to a larger audience. While it cannot be said definitively that such a following did not exist before the internet, the changing modalities and delivery platforms have influenced and largely been responsible in bringing about this wave of cinephiliac desire.

However, Facebook groups like I love trashy hindi movies is not just about obscure small budget films but perhaps speaks to a larger aesthetic or an order of perception that is derivative of the small budget aesthetic of improvisation. The aesthetics of improvisation that a small budget film displays, an aesthetic of interruption where films are interrupted by plot inconsistensies, bad acting, hazy images and an inexplicable excess is deeply embedded in and informs this cinephiliac desire but is also evocative of the industrial practices and informal trajectories that such films undertake. This cinephilia differs from earlier generations of cinephilia in that it is not so much about a physical space and a theatrical experience (a unique experience; every theatrical experience was unique). This new cinephilia is non theatrical; it does not require a visit to the theatre. Instead, it operates from the vast folds of the internet which can be accessed at home or any place with an internet connection. Thomas Elsaesser (2005) suggests that, “what is most striking about the new cinephilia[6] is the mobility and malleability of its objects, the instability of the images put in circulation, their adaptability even in their visual forms and shapes, their mutability of meaning.” And indeed, this wave of cinephiliac desire involves creating new material, transcreating the original both in terms of writing and short video production as I have mentioned in earlier posts. Rather than viewing cinephilia undead (which belongs to Elsaesser’s generation of new cinephilia) as only an engagement with the so-called low genres, an engagement with the obscure and unknown it can be viewed as the cinematic production of a group identity not unlike the Rocky Horror phenomenon, just that cinephilia udead is an online version of that identity.

In this curiosity shop then, all the material that had been transferred to the nether worlds of cinema is being unearthed by its community of aficianados and fans that refuses to let it die. But cinema is, in a sense, made of the undead, imprinted with a specific time and context and functions as an embalmer with a desire for eternal life. So, cinephilia undead is not only governed by a retrospective valorization of small budget obscure films but points towards this form of cinema as the material of film industrial history itself with it’s own industrial logic and definitions of aesthetic.

Credits: Teleport City. Bhoot Ke Peeche Bhoot review by Keith Allison

Credits: Teleport City. Bhoot Ke Peeche Bhoot review by Keith Allison

On the Pleasures of writing about the weird, the obscure and cultural detritus leads to a production of cultural detritus.

I think yes, to a degree. The entire history of cinema has been built on the back of films at which people turn their noses up: horror, fantasy, crime, even sex. These are genres people turn to again and again to test new technology, push censorial boundaries, and to explore what can be accomplished. When the motion picture was invented, it was Georges Melies who first tested the limits of what could be done, and he did it with science fiction and fantasy. When feature films evolved out of shorts, it was again spectacle that tested and expanded limits. Ditto sound, color, widescreen. And yet these genres have always been and continue to be dismissed as being unworthy of serious critical appraisal by most mainstream critics. I think writing about these so-called trash films gives them their rightful and oft neglected place in film history. If they’re trashy or technically crude, it’s because they were navigating uncharted waters. They were raw material. The stuff in the shadows that people derided yet often turned to for thrills and inspiration. I mean, would we have a TV show like The Walking Dead or a movie like World War Z without decades of cheap, crude zombie films? The thrill of writing about these films comes several things, including this “shining of the light on ignored work.” There’s the simple thrill of discovering the forgotten and unknown. There’s the excitement of discovering something you thought would never have been done in a movie of a certain era was being done. And mostly, when you surrounded by a glut of movies that deliver pretty much the same, predictable beats (however competently), trash films, because they were made by people who did not understand or were actively bucking the system, are one of the only places you can go to be surprised or find the audacious. They are films that do things films aren’t supposed to do, and as someone who writes about film, I find that fun and refreshing.

On the adolescent nature/role of humour associated with obscure film commentary

The adolescent nature of humor depends largely on the type of humor, but I agree that yes, to a large extent there’s a certain juvenile strain that runs through a lot of trash film commentary. I won’t guess as to the motivation of others, but for me, humor has been a part of everything I’ve ever done, so it’s only natural that it should surface in my writing. I like to think I’m considerably less juvenile in its execution than I was 20 years ago, when I was younger and first started doing this. But probably not always. It’s a way to break up the technical and artistic commentary on a film. I try to avoid “riffing” or making fun of a movie in a malicious manner, and if I crack a joke at its expense, I hope to surround it by actual constructive criticism. I don’t enjoy mean-spiritedness (though I was guilty of it when I first started out) or humor derived from ridicule. I agree that a certain amount of humor comes from the taboo nature of the material, of sneaking peaks at forbidden things when one is far too young to have been seeing them. Many of us harbor a piece of that sly little kid who thought he/she was getting away with something. Sometimes, humor helps get through a difficult subject — not just a film that is bad, but also a film that deals with sensitive or difficult subjects — either tastefully or not.

References:

- Thomas Elsaesser, “Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment,” Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory, ed. Marijke de Valck and Malte Hagener (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005).

- Srinivas, S.V. “Hong Kong Action Film in the Indian B Circuit.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 2003, volume 4, number 1, April: 40-62.

Notes:

[1] Personal Interview with Keith Allison. June, 2016

[2] Shah Kishan. Personal Interview. Juhu, Mumbai. Kishan is a small budget filmmaker of titles such as Bhoot ke Peeche Bhoot (2003).

[3] Special exhibition slots in which films with adult material were screened in the morning hours before the regular mainstream films. They were popular in the 80s and the early 90s.

[4] Short strips of uncertified celluloid containing pornographic sequences that were attached to the main body of the film clandestinely in theatres which filmmakers used to evade censors.

[5] The small budget Hindi film here is the film that operates in the B-circuit and includes such disparate sub genres as sexploitation, horror, erotica and other so-called low genres.

[6] Elsaesser (2005) suggests there are three generations of cinephilia roughly translating into three different periods the 1960s, the 1970s-1980s, and the 1990s until the present).