This is the fourth and final research note from Charu Maithani, one of the short-term social media research fellows at The Sarai Programme.

This post looks at the various forms of distribution of web based projects starting from 2000, mapping the changing methods of reaching out and interacting with the users.

In the course of the research I have come across several projects that are using different functions of the web, internet, software to create and distribute them to users. These projects allow users to interact, collaborate, re-write and re-mix existing elements of the project or the entire project. In this post, I am discussing a few projects with different methods of distribution.

Distribution or dissemination of web based projects is as important as creating them. In one of my earlier posts I had talked about biennale.py, a computer virus presented in Venice Biennale in 2001. The virus by Mattes in 2001 existed simply because it was circulated by people, knowing or unknowingly. While, certainly the form of the project decides the distribution method. But, in some cases the technical limitations allow only the project to exist in a certain form only. Due to heavy content of images, graphics, text and sound, some of the earlier works could be distributed through CDs only. At the same time not all projects utilise the properties of a distribution method. A project on social media can be low on interaction and collaboration; instead they are largely driven by faster and wider circulation through social media.

Distributed through CDs

Indian Documentary of Electronic Arts (IDEA) was a project between 2000 and 2004 by Shankar Baruah. Baruah, a writer and photographer, had been following electronic (digital) practices (visual and sound) since early 1990s. IDEA was a gazette available and distributed on Compact Discs (CDs). Each IDEA, edited by Baruah, contained text, images, video and sound entries from people all over the world. An extremely rich compilation using video, images and graphics, it was unthinkable for it to exist as a website at that time. Self marketed and distributed in hand made paper covers, the CDs were created through the professional CD making method of stamping/cloning. When the CD could not be made in the auto play mode, Baruah decided to let the contents be in folders. Made in HTML, the user had to click on start.html from the list of files that opened when the CD was initiated. After the first CD, all followed the same format of the content shown in a table and accessible through hyperlinks. This simple yet kitschy, low maintenance design was conceived and executed by Baruah himself. The first CD was priced at Rs 100, but soon the idea of sale was abandoned and the CDs were distributed for free.

With every edition, Baruah presented an editorial outlining its contents. The editions never had a thematic. “It was always a bouquet and never a thematic”, says Baruah[i]. Several Indian digital practitioners like graphic designers, animators, filmmakers and music/sound artists featured with their latest work/project or just their practice discussing several projects together. Global Health Manual (discussed below) by Raqs Media Collective was also featured in its third issue in 2001.

In 2005, all the CDs were complied onto a website (http://retiary.org/idea/) by sound artist and researcher Laurie Spiegel. All editions of IDEA exist on the website in the same format as they did on the CD. The website mounts IDEA as a rich archive featuring the changes brought in different creative fields with the introduction of digital technology. In 2004 Baruah closed this chapter and moved onto CeC (Carnival of e-Creativity), an annual public event for digital creative practitioners.

With its unique collection, Baruah considers each of the editions as artworks.

Distributed through CDs and collaborative/participatory website and software

Raqs Media Collective, an artist collective since 1992, have done projects on the internet in form of websites, CD programmes, software, co-created local networks and installations. The three projects that were distributed in CDs were Global Village Health Manual (2000), No_des (2004) and Ectropy Index (2006). These were run as HTML programs and were produced at the Sarai Media Lab. Global Village Health Manual was co-created by Raqs Media Collective and Mrityunjay Chatterjee. No_des was co-created by Mrityunjay Chatterjee, Raqs Media Collective and Iram Ghufran with additional research by Bhagwati Prasad, Lokesh and Rakesh Singh. Ectropy Index was co-created by Raqs Media Collective, Mrityunjay Chatterjee, Iram Ghufran with research notes by Taha Mahmod.

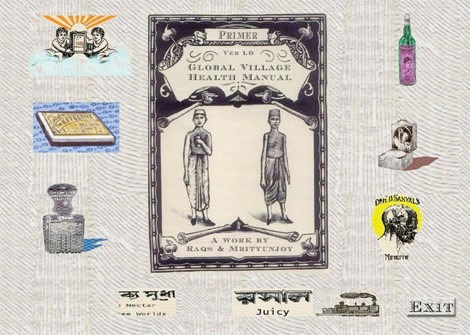

Global Village Health Manual (GVHM) showed a new visual landscape where images from 19th century printmaking and digital images and texts were combined to create an interactive interface. The user could access information by clicking on various hyperlinks. This information collage was created from various sources on the internet and draws a parallel between printmaking in 19th century and the internet. Raqs elaborates “In the late nineteenth century, printmaking entered the public imagination as cheap, accessible and popular means of producing and circulating pictures, stories, information and rumors. This was a culture that eluded censors and skirted copyright. Today, a hundred years later, a cluster of technologies centered on the computer and the Internet has made possible the birth of a new folklore of images and ideas. Which, like its print ancestor, is also busy eluding censors and skirting copyright.”[ii]

Screenshot of Global Village Health Manual

No_des and Ectropy Index followed the format of GVHM. Calling these works as “info-faces” (information interface) the three works were distributed on CDs as the images and text made the pages too heavy to open as a website. Another reason was the unwillingness of people to share images and text and issues of appropriation which have since disappeared with web 2.0.

No_des celebrated practices of sharing, reproducing, editing and distributing information which are labelled as piracy. Texts and images were presented as hypertexts constructing a web of information. Ectropy Index contested the order of information in the system through words linked to text and images.

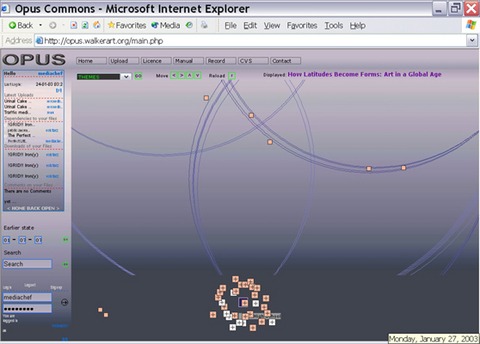

OPUS (Open Platform for Unlimited Signification), perhaps Raqs Media Collective’s most well known web project, was created in 2001 at Sarai media lab. As the name signifies, the online software, opuscommons.net, was an open platform for users to upload their work in form of image, text, video to be used by others. By starting a project, a user could invite others to use the existing media as well as add more files. Every file was uploaded with tags and keywords. The project was based on the idea of ‘recension’ that is reconstructing of the earliest form or forms of an object that can be inferred from the surviving evidence.[iii] In the process of recension, various means of evidence like citations in different languages, sources, its context, time period and association, throws light on the transformation of an object after revision, analysis and destruction. In this project, the uploaded material could be re-used and re-contextualised by anyone. Created in support of the Free Software movement, alluring to downloading, modifying and sharing any information, the project was regenerating ‘digital commons’. It was not only about using information, but also creating works, sharing a common space and co-authoring works.

OPUS constituted the very model of hypertextuality where a web of inter-connectedness determines the proliferation of knowledge, which is the very basis of internet. In fact, OPUS embodies features of web 2.0 where interactivity, re-editing and easy sharing are highlighted. New forms of authorship, relationship with the producer and consumer are emphasized. The re-mix and re-appropriation of content that we see commonly in memes and other forms of internet culture occupy a central thought in OPUS. Lev Manovich, who saw the project in Documenta11, 2002, points out “OPUS project stands out from the rest in how it tackles with the question of authorship in computer culture. Importantly, OPUS, created by Raqs Media Collective (New Delhi), is both a software package and an accompanying “theoretical package.” Thus the theoretical ideas about authorship articulated by Raqs collective do not remain theory but are implemented in software available for everybody to use. In short, this is “software theory” at its best: theoretical ideas translated into a new kind of cultural software.”[iv]

Investing on the features of Opus, Raqs decided to create Apna OPUS at Sarai media lab, for an ongoing project, Cybermohalla, in 2005. Working as intranet, it could be a database of text, images and videos that are available to the community for use. But due to technical issues like slow internet, the project did not generate much interest[v].

Distributed through an interactive website

Archana Hande, trained as a printmaker from Santiniketan, practices in various medium. Known for her tongue-in-cheek humour, her works comment on social behavior of the current times. One of her projects, http://www.arrangeurownmarriage.com/, is a take on arranged marriages in India. The project was eight years in the making and was activated on the world wide web in 2008. The idea of the project was seeded in 2002 during the Gujarat riots. The discussion around identity, purity of race and secularism were the starting point of the project[vi]. Taking a cue from the booming business of matrimonial sites in India, arrangeurownmarriage.com became a satire on the tradition of arranged marriage.

The website gives options to the user to create their partner with face and clothes. An astrology compatibility match is also available. The user can also design wedding invites from the six available design options. The user can choose a religion in which they want to legalise their marriage. There are items that can be shopped for like calendars, postcards and ‘Honeymoon Kits’ that consist of two aphrodisiacs and 4 drawings of bed designs and a book called ‘All About Sex’. These are real items that are made to order by Hande. The last component of the website was the legal aspect which was updated in 2012.

The homepage of the website featuring the close-up of just the fingers of God and man, from the painting Creation of Adam by Michelangelo. This is page exists in HTML and the subsequent pages open as pop-up windows running on Flash. Due to this the website doesn’t open on mobile phones, i-pad and Safari browser. She later presented the project as an installation as well.

Influenced by methods of generative art, computer algorithms and chance, Adityan Melekalam has recently started making web based interactive projects. Cornelia’s Supper (2014) (http://www.adityanmelekalam.com/cornelia/index.html) interrogates the spatial aspect of world wide web. The user views a fragmented narrative on the browser, which is followed by moving the screen in any direction to chance upon dialogues/conversations by a character called Sir Nigel Twitt in the 1950s. Aditya Menekalam trained as a filmmaker from NID, frames form of storytelling in an interactive technological framework. Influenced by Thomas Bernhard’s novel ‘The Loser’, he borrows the name Sir Nigel Twitt from the name of one of the alter egos/pseudonym of pianist Glen Gould. Gould was one of the characters in ‘The Loser’[vii]. The narrative of the story is looped – the same conversations reappear while traversing through the web screen. The project is based on sights of interaction provided in the size of the computer screen.

Distributed and created on social media

The project Delhi Hectic by Arjun Jassal and Azhar Anis makes use of the current functions of the internet in creating and distributing. Using web as a medium for creative expression, Jassal and Anis worked on their Instagram images to create episodes of their experiences in Delhi. Delhi Hectic consisted of various chapters or episodes like ‘This Summer’, ‘Dil-li’ and ‘That’s What He Said’. Each chapter, commenting on different aspects of the city, consisted of 8 – 15 images with text. Sometimes they talked about the people, sometimes about the history of Delhi. The urban yet derelict aspect of Delhi and a satirical take on hip Delhi parties, were a few other topics of Delhi Hectic.

Jassal maintains that Delhi Hectic was a very personal project that got extremely popular. He says, “We started as a personal project but when it got so popular among people, we continued doing it as we enjoyed it. It was not work for us.” Delhi Hectic consisted of 15 chapters created between February 2013 and December 2014. From the ideation of the project to the processing of images and text, the process of completing one chapter took no more than two weeks. About the process of creating and disseminating their project via internet, Jassal comments “Internet works like lego. How people put together the blocks is what matters.”[viii]

Delhi Hectic was first released on Jux – a blogging platform that allowed the project to maintain the feel of a slideshow. Since Jux closed in November 2014, it has been hosted on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/DelhiHectic) with all its chapters. Facebook is not the presentation that was planned by Jassal and Anis, but it works now as the project is over.

An image from ‘Chapter I: An 80s Party’ of Delhi Hectic

Notes:

[i] Baruah, Shankar. Personal interview. 1 Sept. 2015.

[ii] Artist statement on Global Village Health Manual. Shared with the author among programs and images of the project.

[iii] Rescension is part of the critical process of ‘textual criticism’.

[iv] Manovich, Lev, Models of Authorship in New Media, 2002. Web. 3 Sept. 2015.

[v] Bagchi, Jeebesh and Narula, Monica. Personal interview. 6 Aug. 2015.

[vi] Hande, Archana. Personal interview. 17 Aug. 2015.

[vii] Melekalam, Adityan. Personal interview. 19 Aug. 2015.

[viii] Jassal, Arjun. Personal interview. 15 June. 2015.