This is the third research note from Silpa Mukherjee, one of the short-term social media research fellows at The Sarai Programme.

MORTY ROSENFIELD WAS SO STONED on Euphoria, a hot new synthetic drug, that he danced faster than a speeding cursor on a computer screen. It was 3 o’ clock one morning last July at the Limelight, one of New York City’s wildest night spots, and the computer-generated “techno” music was deafening.

-Richard Behar to Time, February 8, 1993, P- 62 [1]

In my previous post I engaged with the circulation of item numbers and their related content on social media focussing on obscenity debates generated by small-time female actors who are prone to viral mutation on the web. Here I shift my attention to another zone of dispersion of item numbers (often live) which is heavily mediated by the digital. This zone of dispersion that I mention capitalises on something that I see as a distinguishing feature of item numbers: loudness. Owing to this loudness, item numbers are appropriated across classes, agendas and spaces. This post thus takes you through the city, with the item numbers sculpting loud neighbourhoods of high-end discotheques, public transport, election campaigns as well as the space of the low brow bazaar.

I feel love…O Munni re

“If you have the right softwares even you can be a DJ”, says DJ Varun, disgruntled engineer who now deejays at Ace of Flames, Hauz Khas Village, New Delhi every Saturday night (Varun is the club’s favourite for its maximum crowd sensation, the Bollywood Nights).[2] Although he prefers playing techno music, Varun does not mind catering to an audience that loves to groove every Saturday to Bollywood songs (“It’s the same crowd that comes every time; rarely do I see new faces”). [3] “…Even three years ago it was difficult for me to mix tracks live, I would simply beat-match and play one masala song after another, I still haven’t thrown away my CDs with extended tracks of “Shalu ke thumke”, “character dheela”, “aa zaara kareeb se” playing in a loop with zero experimental mixing. The idea then was to keep the audience on the dance floor for as long as possible and all that I could do was give them one item number after another by playing pre-mixed tracks with a few added grooves. Live mixing in a club was unthinkable for an ordinary DJ like me…with Macbook Pro and Ableton Live, DJing has attained a new meaning for me, with a few touches I can mix “Babydoll” with David Guetta’s “Li’l Bad Girl”…most of my softwares come from a friend who lives in the U.S, sometimes I purchase them from a Chennai based online store, theinventory.in. I can’t imagine DJing without FL Studio, KOMPLETE Audio 6 soundcard, Logicbook and of course, Traktor. These days I’m experimenting with the iPad, it’s nice you know to get rid of the bulky MIDI controller…there’re a lot of YouTube tutorial videos, we also have an online DJ collective to share information about the latest music apps and DJing softwares…”, says DJ Varun.[4]

Ronald Alexander who deejays in residencies in Bombay pubs and plays only house music says, “When drunk, people make odd requests… “Munni lagao bhai” in the middle of a track from… say Skrillex or Tiesto…my four deck equipment with a Mac with inbuilt MIDI controller and Ableton saves me from many a beer bottles which would otherwise have been hurled on me…nobody uses analog turntables anymore; they’re useless, difficult to handle and very very expensive. By the way, there’s a software named Turntable Pro that works fantastic on Mac, Windows too I guess (Laughs).”[5]

The figure of the DJ now is the cyberpunk hero at its apogee. He is very different from the neighbourhood DJ who pirates low key digital equipment to produce gimmicks at mohalla wedding parades. [6] The new ecology of DJing has ushered in an era of sonic futurism that is extremely indifferent to the human, relying solely as Kodwo Eshun points out on “synthetic recombination technology to amplify rates of becoming alien.” [7] The machine begins to generate new sounds autonomously, without any human touch. The introduction of the first order digital music samplers generated such machinic life forms out of the software. However, with newer innovations within the digital domain, the more savvy softwares have begun to replicate analog functions. This new digitality is a reversion of the tactile logic of analog DJing, in which the finger tips played a role in producing music once again. The fingers now work on a single screen instead of the hardwired setting of a gigantic turntable with multiple scratching devices, with or without preamps. Emulator Pro and Turntable Pro not only emulate the aesthetics of old analog technology but also make DJing more interactive: the mixing desk has now been replaced by a vertical and transparent touchscreen. As Sarah Thornton notes, till the mid-nineties the DJ was hardly a musician, operating as a parasite spinning records tucked away in one corner of the club behind the bulky mixing desk and thus did not have a face. [8] Much later `the cult of the DJ led to the practise of facing the DJ booth while dancing. [9] With the music apps, the Emulator Pro and other interaction generating softwares, the figure of the DJ has attained new connotations; he has become a star with a name as well as a face in his own right.

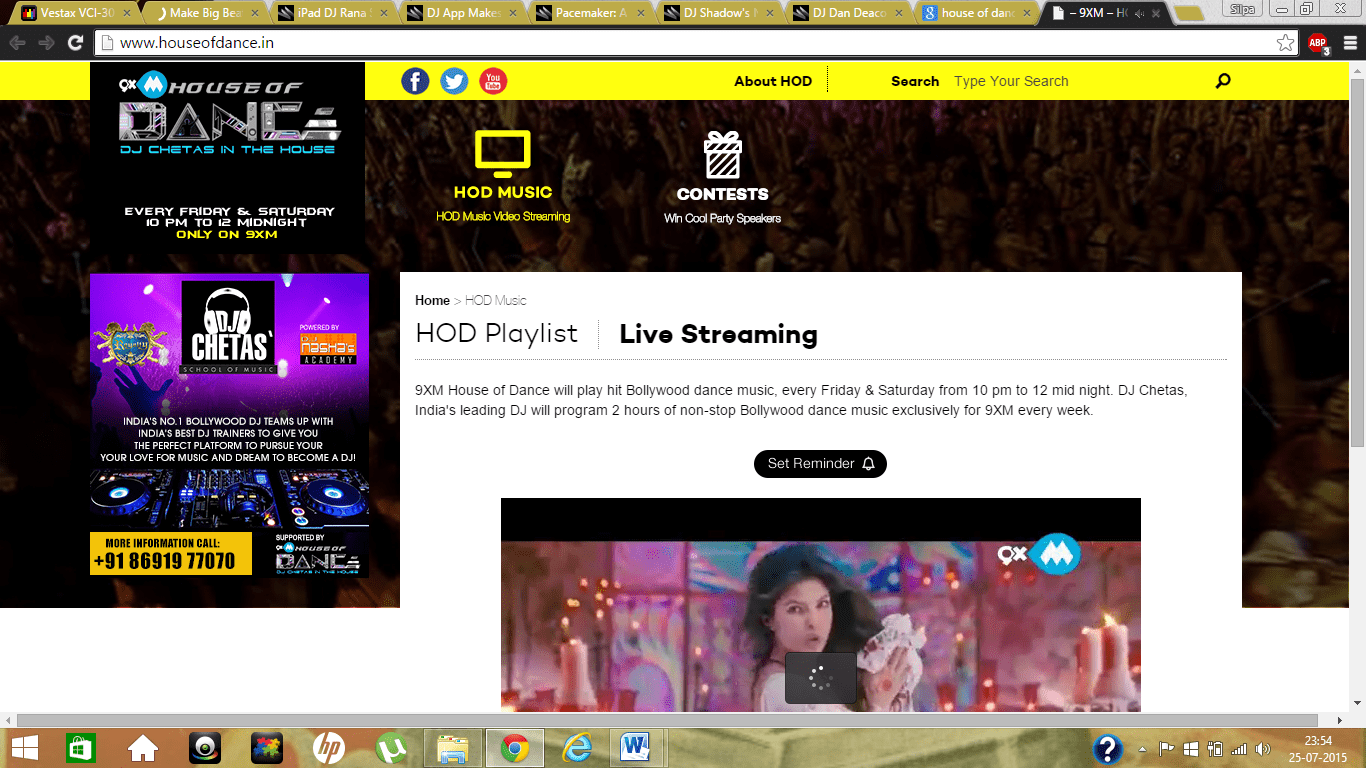

The age of media convergence holds new meanings for the cult of the DJ. 9XM has recently (December 20, 2014) launched a new android app, House of Dance, that aids the user in locating the “happening” dance parties every Saturday night in nine Indian cities. The app also offers live streaming of the 9XM show in which DJ Chetas mixes “2 hours of non-stop Bollywood hits”, every Saturday night between 10PM to 12 Midnight. This is then broadcast on the television music channel, 9XM along with a video remix of the numbers. Every Saturday these two hours are jammed by DJ Chetas on television, YouTube, the HOD app and website as well as at the pub in which he plays live. Televisual exposure also fuels the stardom of certain non-mainstream DJs like DJ Paroma. She is one of the first female DJs in Bollywood who made a name for herself as the official IPL DJ for the cheer leaders with “3-4 lakhs of fan followers over social media” after she interacted with the hosts of the IPL television show, Extra Innings. [10] I refer to her as a “non-mainstream DJ” because she is one of the few DJs in Bollywood to decry software culture; relying very little on video projection behind the console (for which she is dependent on her video editor, Joshua) she increases audience interaction with her own voice over the microphone, and by puncturing the recorded tracks with her sudden use of a live instrument like the violin or a saxophone. [11] She says, “I like giving people goose bumps.” [12] DJ Paroma also capitalises on the fact that she is a woman in the industry; she says, “Let me be honest with you…whenever a female DJ is invited to play in a private party it is mostly for the drama part of it…they say `item ko hi toh item number sabse achi aati hain’”. [13] The presence of a female DJ mixing item numbers in a loud private party adds to the loudness of the environment in general.

A screen shot of 9XM House of Dance, “Ram leela” remixed and streamed live.

Source: www.houseofdance.in

Eduardo Navas notes that remix is of three types: firstly, the extended version of the original track, second, the remix is selective in adding or subtracting material from the original soundtrack but maintaining at the same time the spectacular aura of the original.[14] Finally the remix becomes reflexive when it allegorises and extends the aesthetic of sampling in which the remixed aesthetic surpasses and challenges the aura of the original.[15] This gives birth to the “mashup”. [16] Veteran Bollywood DJ producer, Kiran Kamath who first introduced the concept of the mashup in Bollywood with his Zero Hour Mashup (released by T- Series) at the end of 2011 says, “The craft of DJing is unique for every individual DJ. What I keep in mind while making mashups is that the vocals need to be arranged in a pattern that produces the feeling of a non-stop mix and yet not sound like one single song…There are 16 tracks of every Bollywood song. I look for the tracks that allow me to accommodate the songs by toggling between a range of 90 to 125 beats per minute, (sharp crests and falls in tempo creates jarring noises and can’t be used in a mashup) I also look for hook lines that can be extended…when everything falls into a set, the video editor does a smart mix of the visuals of the songs.”[17] The first remixes in the industry (in the early 90s) were however made on 2 inch tapes: “cutting”, “scratching” and “splicing” the tapes to morph the original. [18] The size of the tape limited the duration of the remixed track. [19]

While the entire exercise of club house music mixed by the DJ for a live audience or remixed and reproduced for distribution over multiple media sites is about sound amplification and the ecology of sensations generated by sound amplification, soundcards and preamps are used to filter the loudness that rises above the background noise of the club, to manage the sensory impact of volume and repetition. This aesthetics of the remix (DJ produced techno music) has influenced the film industry’s song recording techniques. I look at the phenomenon with respect to item numbers in particular. Revisiting Navas’s third distinctive feature of remixes that they challenge the aura of the original soundtrack and have an extended life of their own, a r(ear)view scrutiny of the item number “Aga bai halla machay re” from the film Aiyyaa (dir. Sachin Kundalkar, 2012) reveals how it has incorporated the synthetic aesthetics of techno sound mixing within the original soundtrack. The original song carries two vocal tracks of Monali Thakur and Shalmali Kholgade’s heavily auto-tuned voices mixed with a background track of techno rhythms. The vocals slow down, deliberately slurring and stammering at two minutes and continue with a stammering for the next sixteen seconds as if a DJ has scratched the disc. Kodwo Eshun toys with this concept of a sonic fiction backed by “skratchadelia” which conscientiously wrecks and abuses the human voice to produce mechanical rhythm so that the human becomes a “sono-cyborg”.[20] Scratching writes Eshun, “disarticulates words into blocs of motormouthed texturhythm”. [21] The digital sampling of beats at the junction of two stanzas (at two minutes) of the song “Aga bai”, cracks the human language into phonemes which become “rhythmolecules”. [22] This kind of techno soundscape in the item number to amplify the loudness of the number by morphing the human voice has become popular in the past two years with new auto-tuning softwares and rappers gaining prominence in the film music industry.

“Beach mein thoda Sheila-Munni bhi baja detein hein”

Last winter I was often refused rides by auto drivers in South Delhi. The reason for this was not their regular insolence and idiosyncrasy about not wanting to enter the JNU campus. Rather they were booked by political parties for their election campaigns. Loud speakers and digital music systems playing recorded election jingles in a loop were mounted on the autos. The recorded voice mediated by the music system thus took over earlier forms of mobile election campaigns in which the candidates in person would appear in road shows, speaking and performing to the cheering crowd. The public world of loud sounds is being reimagined in contemporary media assemblages as “previously embodied sounds find new resonances in the plane of the machinic phylum”. [23] One evening a participating vehicle was kind enough to give me a ride from Sarvodaya Enclave to Katwaria Sarai. The driver would not move beyond the crossing at Katwaria nor would he take any money from me. That was his area. A few of them chose to participate in the campaign that spread over three weeks in January, 2015; they were paid a thousand rupees per day for doing the rounds of particular neighbourhoods for eight hours every day.[24] The autos earmarked for the campaign had music systems with two/three USB ports installed in them. They also had loudspeakers fitted onto the roofs. However, the auto drivers were allowed to relax in brief spells to crank up the auditory sensorium of the neighbourhood with music of their choice; the party logic was that one should not bore the neighbourhood with monotonous party jingles. This resonates with Attali’s notion of music where he argues that the mass produced syncretic music tends to censor all other human voices and thus operates as a “silencer”. [25] At the same time this music is “therapeutic, enveloping, purifying, and liberating” in the form of music that has escaped social tutelage: noise. [26] The auto-wallah who becomes a part of the official programme of gigantic noise emission (the unbridled loudness of the election jingle) also becomes the mohalla level DJ, producing a noise of his choice, making his own random selections from his collection on pen drives that he inserts into the player provided to him. When asked if he mixed item numbers too in his playlist, Satinder said, “Haan beach mein thoda Sheila-Munni bhi baja detein hein” (In between I play a little bit Sheila-Munni). [27] Along with the campaign jingles “paanch saal Kejriwal” and its different versions, the neighbourhood could thus fleetingly hear remixes of “Main Zandu baam hui…haan ji haan tere liye” blaring from the autos.

“Jitna saasta phone, utna badiya awaaz”

I was curious about the source of these songs in the pen drives. Two kinds of media circulate in the poorer localities. On the one hand we see an enormous amount of offline content that circulates via the cellular network and is downloaded onto MP3 formats. On the other hand we also see online viewing of content in neighbourhood cybercafés.[28] Online streaming in cybercafés is not the preferred mode in Delhi and Bombay; people download songs from neighbourhood cybercafés and watch it on their personal screens. Owing to the availability of different kinds of cheap music players in the electronic bazaars of these cities, one can hear music booming out of the personal phones of people at crowded and poor localities. In Dharavi, Bombay a line of shops on the main road sell pirated smartphones and cheaper feature phones which support all possible formats. They also offer extremely portable tripod projectors for their phones which cost five hundred rupees at the lowest end. While community viewing of Bollywood songs is restricted to the men in the Sion-Dongri slums, it still regularly features among the few Dharavi pastimes.[29]

Cell phone music is so ubiquitously present in Munirka, New Delhi that along with the regular bazaar noise, it becomes difficult to track the sources of the multiple phones that simultaneously blast music. In engaging a young boy, Prabhu in a conversation, I found that he owns two phones, a second-hand Gionee smartphone and a pirated Nokia feature phone (a fake Nokia phone because it reads NOKAI instead of NOKIA). Prabhu cannot get rid of this fake phone because its inbuilt speakers are deafeningly loud.[30] He says, “(Jitna sasta phone, utna badiya awaaz). The cheaper the phone, the louder its speakers are…When I listen to music, I want the entire mohalla to get to know.” [31] His interesting trivia opens up the media consumption pattern of the poorer localities where loudness in general is associated with a certain kind of public visibility and thus a different order of stardom. Prabhu downloads his collection from a café by the end of that lane and his collections include Haryanvi film songs. The beats of the songs denote that they are dance numbers and the “sonotope” carved by them is similar to Bollywood item number’s; deliberately invested in a hyper-sexualized form.[32] Loudness lends this hyper-sexualized and erotic form an audile quality that is public in nature and yet the cacophony of bazaar noises work towards making that publicness of the erotic in(visible)audible and imperceptible.

In Munirka, I have often witnessed a makeshift open air multimedia parlour on a narrow and overcrowded street. Sangeeta, a female resident of Munirka DDA housing is an enterprising kabadiwala: whenever she gets television, radio, music players in her junk shop she displays them on the street outside and plays them at a high decibel for the others to enjoy. [33] Munirka regulars (which include JNU students, green grocers and other traders, small-time businessmen, and a large floating population of unemployed youth) conveniently occupy the sofa sets that Sangeeta needs to sell, and thus places them outside the shop on purpose. She even fixes the set top box with the television so that potential buyers get a choice of channels. Sangeeta’s floating audience-buyers do not have the patience to sit through any show in its entirety, not even news. They care for nothing other than songs. In a bazaar space like Munirka, the visual register of the songs fail to make an impact on the floating audience. They are drawn to loud numbers with catchy hook lines that sometimes manage to survive the din of the marketplace. These loud numbers with catchy hook lines are inevitably the likes of item numbers.

Sangeeta’s junk shop cum open air video parlour in Munirka Village.

Image courtesy: Shatavisha Mustafi

Notes

[1] Richard Behar’s article on ex-DJ cyberpunk hacker Morty Rosenfield (code named Storm Shadow) “Surfing off the Edge”. Retrieved from a special Time magazine issue on Cyberpunk, digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from R.U. Sirius Archives/Mondo 2000 History Project

https://archive.org/details/cyberpunkvirtual00time

[2] In an interview with DJ Varun, July 19, 2015

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] In an interview with DJ Ronald Alexander, July 24, 2015.

[6] Amit S. Rai and Vebhuti Duggal have worked on the figure of the digital DJ who uses low key pirated equipment.

[7] Eshun, Kodwo. More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. London: Quartet, 1998. P-5

[8] Thornton, Sarah. Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995. P-100

[9] Ibid. p-104

[10] In an interview with DJ Paroma. July 22, 2015.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Eduardo Navas “Regressive and Reflexive Mashups in Sampling Cultures” in Stefan Sonvilla-Weiss ed. Mashup Cultures. Springer Wein, New York, 2010. P-159

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid. p-165

[17] In an interview with DJ Kiran Kamath. July 19, 2015.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Eshun, Kodwo. More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. London: Quartet, 1998. P-15, 20, 26.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid, p-25.

[23] Rai, Amit. S. Untimely Bollywood: Globalization and India’s New Media Assemblage. Durham and

London: Duke University Press, 2009, p- 98.

[24] Retrieved from conversations with members of auto driver’s union in Vijayanagar, New Delhi, July 2015.[25] Attali, Jacques. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Vol. 16. Manchester University Press ND,

1985. p- 9

[26] Ibid. p- 19.

[27] In a conversation with auto driver, Satinder Singh in January, 2015. He helped AAP campaign in Sarvodaya Enclave, New Delhi.

[28] In casual conversations fellow JNU students and hostel mates, Anwesha and Amrapali discussed with me the changing ecology of the cybercafé in a middle class locality in Kolkata. When the line of customers thin out after nine at night, a population of unemployed young boys throng into the café; boys who befriended the assistants of the café owners. I asked Anwesha if the cybercafés then turn into video parlours of older times in which community viewing of pornographic content was the order. She said, “On the contrary these young boys of limited financial means would stream Koka Kola and Paglu on YouTube” (Paglu and Koka Kola are B grade item numbers churned out from Tollygunge, Kolkata). Amrapali added that the cybercafés in Kolkata have reduced in usefulness because not many people would use a public computer for surfing the net any more. Thus they have become the regular haunts of such people who are unable to afford internet connectivity in smartphones or broadband service at home. (July, 2015)

[29] In a conversation with Meenu. Meenu is a Muslim housewife. Her husband (she refers to him as “marad”) is a municipality road sweeper. She says, “We (read women) don’t go there, we’ve this TV, cable connection…I’ve a lot of sewing to do, my elder daughter works in a beauty parlour, younger one goes to school…what’ll we do there (community viewing nights)?” (Dharavi, Bombay, December, 2014).

[30] In a conversation with Prabhu, aged 19, unemployed, semi-literate and lives in Munirka with his family. Munirka, New Delhi, July 22, 2015.

[31] Ibid.

[32] I borrow the term “sonotope” as defined by Jacob Smith to denote the sonic mise-en-scene of certain erotic sequences in this case, the Haryanvi song. Jacob Smith quoted in Brian McNair, “Pornography in the Multiplex” in Hines, Claire, Darren Kerr, ed., Hard to Swallow: Hard-Core Pornography on Screen. Wallflower Press, London, New York, 2012.

[33] In a conversation with Sangeeta in Munirka Village, July 22, 2015.