This is the fourth and final research note from Mrinalika Roy, one of the short-term social media research fellows at The Sarai Programme.

More and more NGOs are joining the online bandwagon. I have mentioned the pros and cons of NGOs going online and the organisations helping them in this endeavour, in my earlier posts. Here, I look at how far going online helped Khabar Lahariya (KL) and whether they have been able to realise all they set out to do.

When KL launched their website in 2013, there were a few things that they wished to accomplish. They wanted their story to reach a wider audience, bridge the gap between rural and urban spaces by taking their stories to the urban online community. They were quite successful in their endeavour and recognised for their efforts, winning the prestigious Duetsche Welle awards for best in online activism [1].

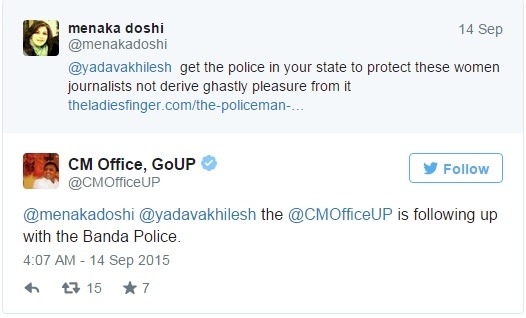

Reaching a wider audience is not just a matter of popularity. It is also a means of righting wrongs. The online community in recent times has emerged as the ‘fifth estate’ that can help bring justice and relief to people. One such person was a Khabar Lahariya reporter. Months ago, Kavita (KL reporter) filed a police complaint regarding a man who was harassing and bullying her via obscene phone calls. The reporter even wrote about her harassment and police inaction. Eventually, the story was picked up by many news agencies [2] and even reposted on the Facebook page of Indian Women Police Network. Matters came to a head when the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister’s Office replied via twitter assuring action, albeit after being called out by journalists. Kavita’s harassment would have ended up being another statistic, had the story not gone viral. NGOs trying to attract attention towards people living on the margins rely and benefit from the ‘viral’ phenomenon. Every ‘like’ and ‘share’ acts like virtual currency, furthering their cause.

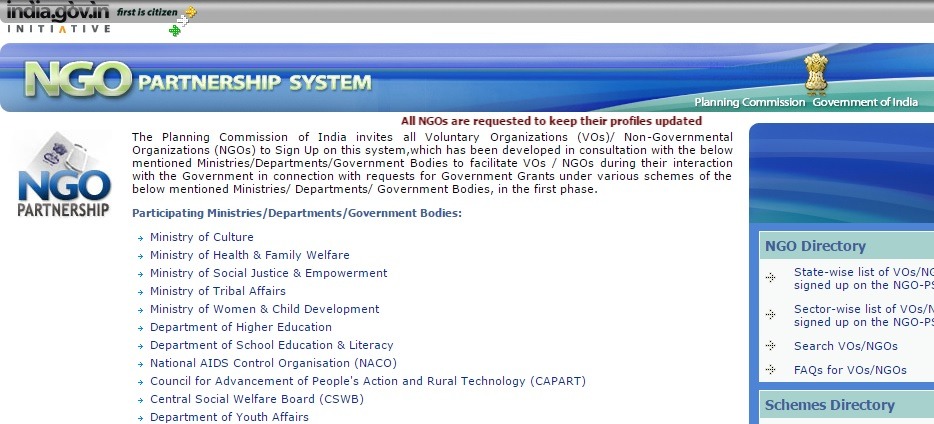

Speaking of currency gain, it’s no longer just metaphor. Online presence has helped NGOs monetarily and Khabar Lahariya is not an exception. The NGO Partnership System [1] – an initiative of the Govt. of India’s Planning Commission – is a prime example. It is an online platform bringing together various ministries and NGOs. All one has to do is register ones NGO on the portal, to be eligible to apply for grants made available by different ministries. It is a forum making the economy of running an NGO easier. But, government grants are limited and fiercely contested.

NGOs like Khabar Lahariya are now using internet for attracting individual donations as well. KL’s reporter sponsorship programme is one such example. This year, Khabar Lahariya started its new mentoring programme. The online community was asked to pitch in and sponsor Khabar Lahariya reporters. People can donate a lump-sum amount that would go towards a reporter’s training and salary. According to KL members, the programme has received a positive response and many people have donated money. KL has managed to not only incite interest, garner support online but also use it for furthering its cause. Such measures also ensure that people are intimately connected to KL’s vision.

In 2014, movie critic Anupama Chopra donated Rs 1 lakh to the organisation. I am not aware of all the details but it would not be to presumptuous to deduce that KL’s online presence helped get its work noticed by the film critic. Prior to 2013, such magnanimity would have been difficult to come by. Also, and more importantly, the organisation was able to widely promote this piece of news. It is safe to say that many monetary offers that followed suit were partly thanks to it.

Boys, Smartphones and Video Clips

One of the primary goals of the Khabar Lahariya’s online venture was e-literacy in rural areas especially among women. It was believed there was a pool of people in rural areas who have recently joined or are eager to join the e-community. The objective was two-fold – make people e-literate and as a corollary to that get a steady supply of readers for the Khabar Lahariya website. “People living in small towns and villages are becoming tech-savvy. We want to tap into this area. Also, the content on our website is designed to cater to the villagers,” said Shalini, managing director of Khabar Lahariya. It was felt that the website will provide information to the villagers. Yet, the reality has failed to live up to the goal.

It emerges there are two impediments in Khabar Lahariya’s path – lack of access and interest. The villages around Faizabad offer a perfect example of irony where people have internet-enabled phone but no internet access.

Majority of the youth in the village (to be more precise, let us say young men) own smartphones. The popular brands include Lava, Blu, Intex, Posh and Yezz. On my field visit to Jarehi (30 km from Faizabad district centre), I saw teenage boys lying on charpoys outside their houses, whiling away the afternoon absorbed in their cellphone screens, not unlike most youngsters in urban areas. These are mostly purchased from the nearest big town (in this case Faizabad). Om Prakash owns one such mobile shop on the outskirts of Faizabad. His shop is stocked with low-priced cellphones. “My biggest clientele nowadays are people from small towns and villages around Faizabad, mostly young men looking for cheap smartphones. They all want camera phones with internet access,” the owner explained. Clearly, the mobile revolution has reached these hinterlands. Yet, access to internet remains precarious. Possessing an internet-enabled phone does not connect you to the world.

Mobile shops, not unlike internet cafes, are all located in big towns or the main market in the kasba. “Earlier, we had to travel to the nearest town to recharge phones. Thankfully, things have changed for the better. Many local shops now keep recharge vouchers. However, we still have to go to either Faizabad or the main village of the kasba to get internet recharge,” explained Sangeeta, one of the KL reporters. In Jarehi, I saw local pan shops and tea stalls doubling up as recharge outlets but none of them offered phone data recharge. Irregular internet access stalls development of e-literacy and e-curiosity. The seamless internet access that Khabar Lahariya team members envisioned is absent. Access to internet remains gendered and suffers from infrastructural problems.

The second assumption that once rural people have internet access, they will make use of the Khabar Lahariya website is also belied by evidence. “Do you think these young boys will access the Khabar Lahariya website, read the articles and share them with others?” asked Sangeeta mockingly. She has a point. The mobile owning demographic is primarily male and young. Internet is used only as a means of entertainment. “Many village boys come here to access internet, download songs and video clips on their phones,” said Om Prakash, who also runs an internet cafe inside his mobile shop. Om Prakash was discreet enough not to divulge what kind of video clips the men usually access but became ambiguous and shielded once asked if pornographic clips were also circulated among the clientele. Clearly, these boys have zero interest in a website like Khabar Lahariya. The older generation as well as women who might find the website useful lack access while those who have access lack the inclination.

Notes:

[1] – https://thebobs.com

[2] – The Policeman Said: Why Don’t You Tell Me What Gaalis He Whispers in Your Ear? – Published on The Ladies Finger. http://theladiesfinger.com

[3]– http://ngo.india.gov.in