This is the third research note from Pallavi Paul, one of the short-term social media research fellows at The Sarai Programme.

Entering the cyber cell of the Economic Offences Wing (Delhi Police) is like walking into a time lag. One of the few air-conditioned rooms in the Mandir Marg police station building, it sits on the second floor, just above the desks of investigating officers on the lower floors pouring over heaps of paper, summoning complainants and defendants to record their claims in handwritten notes and dust ridden case files. Incessant ringing of landline phones, constant chatter, groups of people huddled together, open windows, tea stained table tops and the slow churning of fans- the ‘texturology’ of the cyber cell stands in sharp contrast to the spaces one encounters immediately before walking through its doors.

An assortment of mundane digital objects like hard drives, CD writers, chipsets, computer monitors, wires and cables lie together in this quiet sanitized room filled with cold fluorescent light. Wittgenstein’s time world comes rushing at us as our instinctive familiarity of these digital objects, alongside their display as ‘yet to be unpacked’ crime exhibits, makes one oddly aware of the duration that passes before being able to perceive an object.[1] And even as one does, it seems too late. Examining these objects in this room, feels akin to their death, something that can be done only when the entire career of the digital object is already behind it. As strategy then, while seized/ceased objects are frozen in their found state, their ‘data images’ are allowed to proliferate and live out their phantom lives during investigations.

In an interview held at this office, Inspector (IT) Mr. Vijay Gehlawat noted , “As standard procedure, whenever we find a device that needs to be seized, we never alter its found state. If it is switched on, we leave it on and vice verse. In case of computers, we pull out the power plug directly so that the process does not get time to shut down”. He elaborates, “after coming to the lab we don’t work on the seized device at all. We send it to the Forensic Science Lab and retrieve its data image. It is only on this image that we continue to do our investigations and experiments .” [2] Mr. Vijay Kasana, Sub Inspector at the Cyber Lab explained the process further, “During the process of creating a data clone/copy from any device it is very important that we get a hash value certificate ”. [3] A hash value is a result that that is computed after running a calculation algorithm on data files. These can be any kind of electronic files including text, image, sound etc. The algorithm generates the “thumbprint” of the contents which can then be compared using several high speed hash engines like ‘pinpoint harvestor’. In simple terms the hash value of an electronic file is its digital fingerprint. In his discussion on the admissibility of hash value in Indian courts, lawyer Neeraj Arora states that for the admissibility of forensic evidence in court hash value has to be computed at least three times at different stages of the investigation. “First Hash is calculated at the time of the acquisition of evidence so that authenticity and integrity of the evidence can be establish in the court of law by comparing the such Hash value with the Hash value calculate at any stage or before the court. The second Hash value is calculated of the image which on comparison with the Hash value of original evidence will prove the authenticity of the image so prepared and also the subsequent evidence or artifacts extracted from such evidence. The third Hash value is calculated of the original media after imaging to established that the original media has not been altered in the preparation of forensic backup”.[4]

Even as the algorithms of data mining and authentication seem to get more precise, the experience of presenting forensic evidence in court still seems clouded with anxiety and doubt. Inspector IT Mr. Vijay Gehlawat said, “ In courts, forensic evidence is still considered secondary to primary or physical evidence. There have been so many cases in which we have shown the judge the exact algorithm for enhancing CCTV footage, done a live demonstration the technique also, but if he/she is suspicious of the technology involved or has decided to not take it into account, our efforts prove to be useless in the absence of primary evidence. In the five minutes that we are accorded in front of the judge, a lot depends on his/her openness or willingness to understand the technicalities involved. ” [5]

In a report published by the Delhi Police it was noted that between the years 2011 to 2014, the number of cases registered under the IT Act rose from 50 to 169, these mostly dealt with post/e-mails generally related to social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter & Youtube, fake e-mail IDs, hacking of websites/e-mail accounts, credit card frauds, Internet banking, frauds, abusive/ defamatory/threatening e-mails”. In contrast to this less than ten convictions have happened under the IT Act (2000), after nearly 15 years of its existence. “Sometimes this is very discouraging for the investigators. Since even the inception of this cell in 2000 and my recruitment in 2006 we have solved the toughest cases made several arrests, but we have not been able to achieve a single conviction. The way I see it, our job is to keep the standard of investigation high and learn more from latest forensic methods adopted in countries like USA”, said Mr. Gehlawat.[6]

Reminiscing about a major case where email hacking, SIM card fraud, identity theft, cross border money laundering and cell phone hacking was happening at once, he said that in 2012 an FIR was registered in the Economic Offenses Wing, by a resident of Defense Colony in Delhi. The complainant claimed that an amount of Rupees Twenty Lakhs was transferred from his private account at YES BANK through fraudulent means on the night of 19-20, Oct-2012. Further, his mobile phone had been mysteriously deactivated for the duration of the transfer and it was only after he got his phone reactivated that he found out about the missing amount. A detailed investigation followed by a team comprising of Sub Inspector Kanhaiya Lal Yadav, Assistant Sub Inspector Sunil Malik, Head Constable Daleep Singh, Head Constable Rati Ram, Constable Ravinder, Constable Manoj Kumar, Constable Randeep and Inspector Gehlawat himself. It was through monitoring of cell phone records, examination of IP logs and ground level enquiries on the whereabouts of the suspects that the case was finally solved and the accused apprehended. Investigations revealed that this was the work of a gang spread across several Indian cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Gujarat and Meerut. First the primary accused would use the help of his Nigerian aides to get the user ids, passwords and bank details of various people. This would be done via phishing, identity thefts and email hacking. Then fake accounts would be opened by gang members in various banks, these would be used just once to receive the transferred money and then left inactive. Finally the gang would tie up with mobile service providers to deactivate the SIM card of the target and apply for a duplicate one, which was then used exclusively for the duration of the fraud. This would then be used to intercept the One Time Password sent by the bank when requested for the transfer. Once the transfer was successful, cash was immediately withdrawn from the fraudulent accounts and each remember would get their share according to a pre-decided break up.[7]

Interviews with officers at the cyber lab revealed that there has been a stark shift in the nature of complaints being received by the cyber cell over the last few years. Earlier the services of the cyber cell were mostly sought by individuals/ businesses/ institutions targeted by technically proficient hackers, however, now most cases relate to the circulation of ‘objectionable’ content on social networking sites and messaging services like WhatsApp and messenger. A huge reason for this , Mr. Kasana notes, is the availability of reasonably priced Chinese phones and cheap data packs offered by mobile service providers. Most of the content being uploaded on these sites is coming from mobile phones, and our task becomes even more complicated when hate messages or objectionable images start circulating on these platforms on a large scale.[8]

Laying out the basics of GSM mobile phones and network forensics Svein Yngvar explains that evidence can be mined from three primary sites- the mobile equipment, the SIM card and the core network. Developed between 1988-1990, GSM (Global System for Mobile Communication) is the largest system for mobile communications in the world. It is a fully digital system, allowing both speech and data services and allowing roaming across networks and countries. To understand the manner in which forensic investigation of mobile phone data is undertaken, it is important to trace the GSM chain.

The first interface for data mining is the user equipment or the mobile headset. This is the only part of the GSM chain that is actually visible to users of the network. The second significant link in the chain is the SIM (Subscriber Identity Module). This is a smart card with a small processor and memory,that uniquely identifies a user to his/her network. The Base Transciever System (BTS) is the site that communicates between mobile stations. A BTS would typically have several antennae each of which intercept a particular frequency. The Base Station Controller (BSC) controls several hundred BTS’s, it takes care of a number of different procedures regarding call setup and location update . Finally the Mobile Switching Centre deals with switching speed, data connections and the movement of users within different GSM networks.

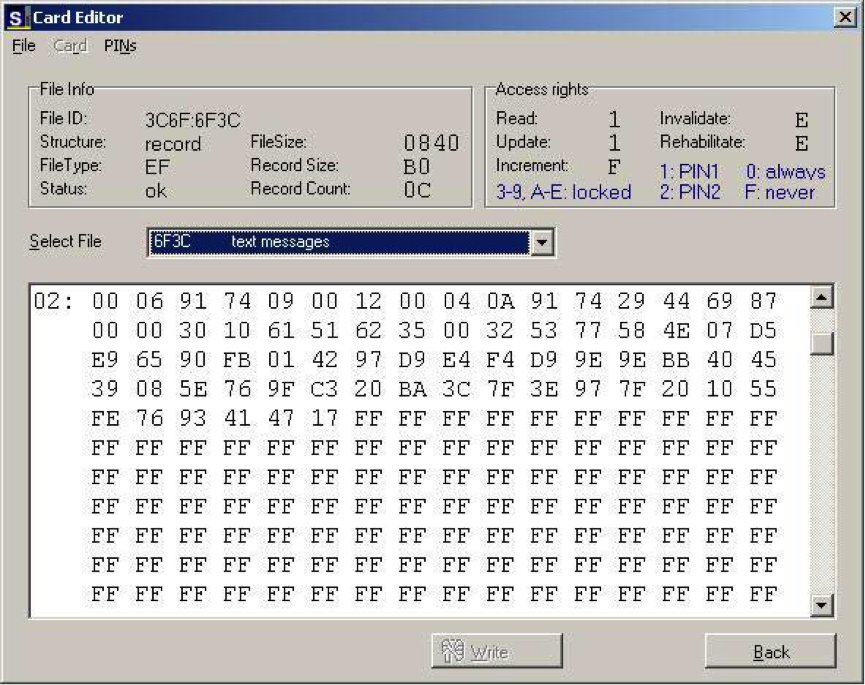

In cases where SIM cards are retrieved from the crime scene, these cards are loaded onto SIM readers to download the entire memory of the SIM. Then a hash value is generated for this memory

Amongst the several kinds of files that are present on the SIM memory is the Location Area Identifier (LAI) this contains information about the last used location of the headset. The other kinds of information that can be retrieved through a forensic analysis of the SIM card and the mobile headset includes- Call records, saved SMSs, Customer name and address, Billing name and address (if other than customer), User name and address (if other than customer), Billing account details, Telephone Number (MSISDN), SIM serial number (as printed on the SIM-card), PIN/PUK for the SIM and services provided to the user.[9]

While modifications to the memory contents of mobile headsets and SIM cards, popularly known as ‘flashing’ can pose significant problems for forensic investigators, the retrieval of deleted content from services like WhatsApp is also undertaken by investigators in cases where the content in question is no longer available in the memory of the device or the SIM card.

Writing on WhatsApp forensics Neha Thakur [10] and Shubham Sahu [11]explain that in android phones the data exchanged between users on WhatsApp is hosted on a SQLite database. SQLite is a popularly used data base engine originally developed for the US Navy in 2000. The main feature of this database is that it can house several processes in a compact engine without the need for a overhead process management system. Further, the code for SQLite is in the public domain and can be used by any person/organization for its own purposes. The database in which WhatsApp messages were previously stored was ‘msgstore.db’, however, in the interest of greater security of the data of their users, whatsapp has now started encrypting its data making the file ‘msgstore.db.crypt’. Once the encrypted WhatsApp data base is accessed through the SIM card, ‘WhatsApp extract’ , a decryption tool helps the investigators retrieve all the information including deleted messages and photographs and clips as thumbnails, in an easily accessible HTML format.

While it is possible to retrieve hidden or deleted data from the mobile hardware, there are several cases in which investigators have no access to either the sender or the device through which implicated content is circulating. During discussions with officers at the Cyber Lab I was pointed towards a 2014 case in where a 24 year old MBA student Syed Vaqas was arrested in Bangalore for sending a WhatsApp message to Jayant Tinekar, an activist from Belgaum. The message consisted of a morphed picture where the final rites of Narendra Modi are shown being performed in the presence of L.K Advani, Rajnath Singh, Sushma Swaraj, Baba Ramdev, Maneka Gandhi and Varun Gandhi. The caption accompanying the photograph said – ‘Na Jeet Paye Jhooton Ka Sardar — Ab Ki Baar Antim Sanskar (A false leader will never win, this time it’s final rites). On receiving such a message, Tinekar who had no previous acquaintance with Vaqas, filed a complaint at the Kanapur police station at Belgaum. Acting on his complaint, the phone number was traced to Bangalore, from the number the police determined the tower location in Vasanthnagar and finally to Vaqas’ cellphone. Vaqas was booked under IPC sections relating to hurting religious sentiments and under the Information Technology Act, 2000.[12]

Of late several instances of mass circulation of hate messages, pornographic content etcetera through WhatsApp have surfaced in several parts of the country. In September 2014, an alert was sounded in Allahabad when shortly before the by-election, a WhatsApp message warning people against love jihad began to circulate widely.[13] In the same year, a similar incident occurred in Maharashtra when Abdul Hafeez a resident of the Sillod district in Maharashtra, filed a complaint about a WhatsApp message being circulated by a group titled ‘Happy Diwali” which urged Muslim girls to marry Hindu boys.[14] Explaining how such matters are usually dealt with, Mr. Gehlawat said, “ It is next to impossible for us to stop the circulation of messages on WhatsApp, even though in many cases we do write to Facebook as now they have bought WhatsApp informing them about the culpability of certain content. The procedure that we do follow, however, is that in the case of a complaint we start investigation from the last sender of the message. It is only when someone is found to be a sender of objectionable content, that an enquiry can be initiated against them.” He further added, “ Sometimes if the message is circulating in a small group of 10-20 people it is possible to nab the primary sender, but this is very rare.”

It is also important to point out that while many complaints of this nature come to the cyber cell on a regular basis, a majority of the complainants refrain from pursuing the matter in court. In a recent survey on the harassment via WhatsApp in urban and rural India, Debrati Halder and K. Jaishanker point out that there seems to be a reluctance in people to report harassment that occurs through messaging platforms like WhatsApp. Further, a majority of people are not even aware that forwarding certain kinds of images, texts and videos could be a criminal act.[15]

Echoing the findings of the report, Mr. Kasana recounted a recent complaint in which a daily wage worker sought police intervention as his immediate neighbor was forwarding photographs of his daughter to her prospective husband on WhatsApp. “ It was a case of revenge by the girl’s ex-lover, however, we couldn’t register a case as these were not obscene photographs. They were pictures taken of the girl and him at India Gate.” “The father of the girl, did not want to press the matter further but urged us to call the prospective groom to tell him that the photographs were possibly morphed.” He added, “These kinds of requests for interventions come to us all the time , where complainants seek police pressure to stop harassment without following up the matter in court.” [16]

Notes

[1] Park, Byong-Chul. 1998. Phenomenological Aspects Of Wittgenstein’s Philosophy. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

HINTIKKA, JAAKKO. 1996. ‘Wittgenstein On Being And Time’. Theoria 62 (1-2): 3-18. doi:10.1111/j.1755-2567.1996.tb00528.x.

[2] Gehlawat, Vijay. 2015. Cyber Forensics in India Pallavi Paul Interview by . In person. Mandir Marg, New Delhi

[3] Kasana, Vijay. 2015. Cyber Forensics in India Pallavi Paul Interview by . In person. Mandir Marg, New Delhi

[4] Arora, Neeraj. 2015. ‘Complete Information And In Depth Analysis Of Financial And Cyber Forensic. Including The Various Legal Ways To Tackle Financial, Cyber And Share Frauds With Various Legal Forms And Investigating Authorities.A Platform To Discuss & Analyse Financial And Cyber Forensics’. Neerajaarora.Com. http://www.neerajaarora.com/.

[5] Gehlawat, Vijay. 2015. Cyber Forensics in India Pallavi Paul Interview by . In person. Mandir Marg, New Delhi

[6] Ibid

[7] Delhi Police,. 2013. ➢ Kingpin Of A Well Entrenched Racket Of Internet-Banking Frauds Arrested.

[8] Kasana, Vijay. 2015. Cyber Forensics in India Pallavi Paul Interview by . In person. Mandir Marg, New Delhi

[9] Willassen, Svein Yngvar. 2003. ‘Forensics And The GSM Mobile Telephone System’. International Journal Of Digital Evidence Volume 2 (1).

[10] Thakur, Neha.S. 2013. ‘Forensic Analysis Of WhatsApp On Android Smartphones’. Ph.D, University Of New Orleans.

[11] Sahu, Shubham. 2014. ‘An Analysis Of WhatsApp Forensics In Android Smartphones’. International Journal Of Engineering Research 3 (5): 349-350.

[12] Swami, Chaitanya. 2014. ‘Youth From Bhatkal Arrested For Sending WhatsApp Message On Modi – Bangalore Mirror’. Bangaloremirror. http://www.bangaloremirror.com/bangalore/crime/Youth-from-Bhatkal-arrested-for-sending-WhatsApp-message-on-Modi/articleshow/35610511.cms.

[13] Dixit, Kapil. 2014. ‘Cops Alert After Circulation Of Messages On ‘Love Jihad’ – The Times Of India’. The Times Of India. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/allahabad/Cops-alert-after-circulation-of-messages-on-love-jihad/articleshow/40874898.cms.

[14] Twocircles.net,. 2014. ‘Anxious Sillod Muslims Awaiting Police Action Against Circulation Of Derogatory Posts On Whatsapp | Twocircles.Net’. http://twocircles.net/2014oct27/1414425022.html#.VcnC3hOqqko.

[15] Haldar, D. 2015. ‘Harassment Via Whatsapp In Urban And Rural India: A Baseline Survey Report (2015). Tirunelveli, India: Centre For Cyber Victim Counselling.’. Academia.Edu. https://www.academia.edu/10610223/Harassment_via_WhatsApp_in_Urban_and_Rural_India_A_Baseline_Survey_Report_2015_._Tirunelveli_India_Centre_for_Cyber_Victim_Counselling.

[16] Kasana, Vijay. 2015. Cyber Forensics in India Pallavi Paul Interview by . In person. Mandir Marg, New Delhi