This is the second research note by Ankush Bhuyan, one of the researchers who received the Social Media Research grant for 2016.

In the first part of this two-part post, I aim to give a brief political history of the Bodoland movement which lays the ground for the rise of social media that has come to both inform and participate in the political situation in the region. The growing role of social media, as I see it, continues to reach out to a larger audience who take an interest in the movement for numerous reasons. Popular social media websites like Facebook and YouTube, which I focus on, have become points of dissemination for various types of news and information, thereby making it a multi-purposive platform.

A Brief History of Bodoland

The Bodos are a tribal people primarily located in the North-western part of Assam, on the northern bank of the Brahmaputra River. However, Bodo people also live in various pockets of Assam, West Bengal and Nepal.[1] The group was historically disenfranchised from its land because of land administrative practices introduced by the British which sowed the seeds of conflicts between the Bodo and non-Bodo people, the latter primarily being the Muslim migrant population that has settled in the area.[2]

The problems based on land acquisition and control escalated after Independence as the Bodo did not find any recognition of their right to their land. In the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution in 1950, Bodo people were denied the provisions under which they could have had greater administrative power over their territory through an Autonomous District Council.[3] The councils were constructed in such a way where land and tradition of tribal groups could be protected as they were given control over certain provisions. The denial of this power further created a sense of wrong among the Bodo people and this continued to grow in the coming years. The creation of the Plain Tribals Council of Assam (PTCA) in 1960 provided a platform for their demands to be forwarded. However, the PTCA was plagued with inadequacies in its administrative structure that made it inefficient. The Assam Movement from 1979-1984 led by the All Assam Student’s Union (AASU) had the participation and support of Bodo people because of its anti-outsider agenda.[4] The success of this movement gave the Bodo people hope that the newly formed state government by the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), formed out of AASU, would help their cause. However, in a couple of years the Bodo leaders felt the same kind of apathy towards their demands. This realisation was the turning point as the Bodo People Action Committee (BPAC) and the All Bodo Student Union (ABSU), styled after AASU, in 1987 began their demand for a separate state by calling for ‘divide Assam 50-50.’[5]

The consolidation of the Bodo identity through the desire to have greater control over their land against the domination of Hindu Assamese and migrant non-tribals (primarily Muslims and Bangladeshi migrants whom they saw as encroachers) pushed them to take drastic measures.[6] The death of Upendra Nath Brahma, one of the revolutionary leaders of the movement, in 1990 saw the rise of the militant group, Bodo Security Force (BrSF). The first wave of violence began in 1989 where Bodo activists kidnapped, bombed and killed, leading to the death of 350 people, the movement for a separate state witnessed escalating incidences in violent outbreaks. As the movement turned increasingly militant, a Memorandum of Settlement was signed in 1993 between BPAC, ABSU and the central government, which came to be known as the Bodo Accord. It gave control of 2,570 villages to the Bodoland Autonomous Council (BAC) without either a precisely demarcated boundary nor financial independence.[7] The Bodo Accord did not change the ground reality of the territory or the people and was seen as a tool to pacify the militants and separatists. Eventually, other violent separatist groups such as Bodoland Liberation Tigers (BLT) and National Democratic Force of Bodoland (NDFB) continued their struggle for a separate state.[8] A second accord was signed after ten years in 2003 between the Assam Government, the Indian Government, and the militant groups from which the Bodo Territorial Council (BTC) was created through the amendment of the Sixth Schedule, that included the Bodos and gave BTC administrative powers over the districts of Kokrajhar, Baksa, Chirang and Udalguri on paper. The Bodo leadership considers this accord a compromise as they continue to lack financial autonomy.

The districts under BTC are fraught with tension as several ethnic communities, like the Bodos, the Rabhas, the Santhals, the Koch-Rajbongshis, the Nepalis, the Assamese and Muslims, live in close proximity to each other and run the risk of treading on each others shoes. We have to take into cognisance that the figure of the ‘migrant’ has played a crucial role in the identity politics of the region and the way it has been mobilised in electoral politics.[9] Identity politics has shaped and coloured much of the contemporary narrative, imagination and perception, from inside and outside, of the North-east region. Anwesha Dutta writes that the Bodo identity hinges on the notion that they are different from the dominant Hindu Assamese and other tribal groups and migrants who they see as encroachers upon their land.[10] She has highlighted the recent clashes the Bodos have had with other minority groups in the region apart from the ruling Assamese community. Dutta writes that this precarious position highlights that the Bodos are both anti-hegemonic and at the same time do not acknowledge other disenfranchised groups.

Mobilising the Bodos via Social Media

Social media has become a powerful platform around the world to connect, communicate and forward ideas, ideologies and politics.[11] Manuel Castells has theorised through numerous examples how networks, information and media in the global age foreground the issue of identity through various social and political movements. He provides the example of the Zapatistas from Mexico who used media platforms to communicate to people about their struggle, which was for the control over their resources and their land, and against the ‘organised crime’ unleashed on them by the dominant groups in power.[12] The methods that they used to communicate their message led to widespread support for them and an eventual negotiation with the Mexican government. Similarly, I feel that there is a mobilisation of the Bodo identity, homeland and a sense of Bodo marginalisation through various media platforms. The political discourse focuses on the violence and uncertain reality under which the Bodo people live.

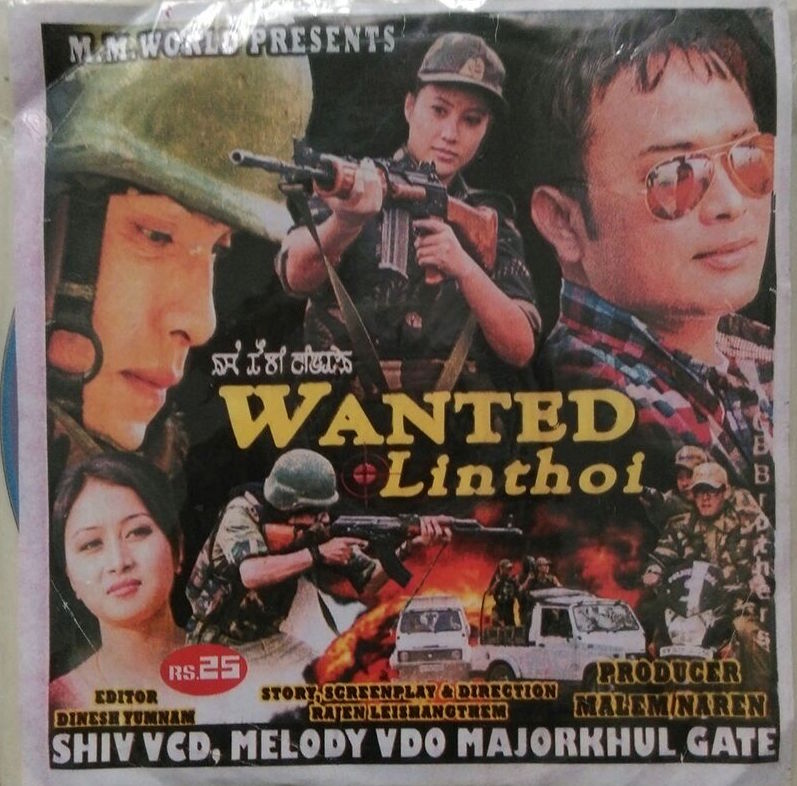

Fig. 1. THE BODOS, a Facebook page, which has regular posts that indicates the marginalisation felt by a certain section of the Bodo community from the dominant Assamese community. See “The Bodos.” Facebook. Facebook. 7 Feb. 2016. Web. 10 Feb. 2016.

Fig. 1. THE BODOS, a Facebook page, which has regular posts that indicates the marginalisation felt by a certain section of the Bodo community from the dominant Assamese community. See “The Bodos.” Facebook. Facebook. 7 Feb. 2016. Web. 10 Feb. 2016.

On Facebook, there are pages like THE BODOS, Bodoland Today, Bodoland Sansri, The Great Bodoland and others that highlight the current events from the region and news of Bodo people.[13] There are only a few local Bodo newspapers and no dedicated television channel focusing on news from the BTC region, in which case blogs and Facebook pages have become the carriers of news and information to a wider audience.[14] The articles and posts are primarily in the English language and not in Bodo. THE BODOS is one of the most active pages and it has more than three thousand ‘likes’ or followers. The Bodoland Sansri, which is in Bodo language and has titled itself as a daily, has not been active on Facebook since September 2015 even though it has a following of more than thirteen thousand people.[15]

Fig. 2. Two Bodo youths killed by the army that was posted on THE BODOS. See The Bodos. “#TearsNeverStopFalling in Bodoland” Facebook. Facebook. 16 Feb. 2016. Web. 18 April. 2016.

Fig. 2. Two Bodo youths killed by the army that was posted on THE BODOS. See The Bodos. “#TearsNeverStopFalling in Bodoland” Facebook. Facebook. 16 Feb. 2016. Web. 18 April. 2016.

Fig. 3. A NDFB(S) militant killed in the joint operation by the army to uncover one of its base camps. See Archiving the Bodo Conflict in Assam. “NDFB-S hideout busted and one top NDFB-S neutralized in Ripu RF.” Facebook. Facebook. 12 May. 2016. Web. 14 May. 2016.

Fig. 3. A NDFB(S) militant killed in the joint operation by the army to uncover one of its base camps. See Archiving the Bodo Conflict in Assam. “NDFB-S hideout busted and one top NDFB-S neutralized in Ripu RF.” Facebook. Facebook. 12 May. 2016. Web. 14 May. 2016.

THE BODOS focuses on cultural and political developments, news and opinionated posts that concern Bodo people and the BTC, see fig. 1. In the description section of their Facebook page, it is stated that “This platform is for people who have a heart for Bodoland and those who want to liberate it to freedom from the political entrapment of the Indian state.” In the #TearsNeverStopFalling in Bodoland post, it carried pictures of two dead Bodo youths who were allegedly from the NDFB(S) militant group, and they were brutally killed by the Indian army in a fake encounter, see fig. 2.[16] Along with the write-up accusing the army and government of the killings, the comments section on this post expressed outrage by readers who discussed issues of human rights and electoral politics. Another Facebook page called Archiving the Bodo Conflict in Assam (ABCA), focuses on terrorist activities and conflicts. It also carries graphic pictures of a Bodo ‘terrorist’ of the NDFB(S) killed by the army, see fig. 3. The position of both these pages on Facebook, THE BODOS and ABCA, is markedly different as the former is critical of the BJP, the political tug of war, killing of ‘innocent’ youths while highlighting the cultural vibrancy of the Bodo people, while the latter focuses on the militant activities from the region. The posts by ABCA are often about news of the army apprehending Bodo militants which are accompanied by pictures, see fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Snapshot of NDFB(S) caught by the army. See Archiving the Bodo Conflict in Assam. “NDFB-S cadres caught by 7 Sikh Light Infantry in Runikhata , Chirang on 21 May.” Facebook. Facebook. 21 May. 2016. Web. 28 May. 2016.

Fig. 4. Snapshot of NDFB(S) caught by the army. See Archiving the Bodo Conflict in Assam. “NDFB-S cadres caught by 7 Sikh Light Infantry in Runikhata , Chirang on 21 May.” Facebook. Facebook. 21 May. 2016. Web. 28 May. 2016.

With the news coverage of frequent conflicts between the army and banned terrorist outfits like NDFB(S), there is a sense of turmoil and tension in the region. On YouTube, a quick search shows many videos hosted by different news channels carrying news of the conflicts in Bodoland. I also came across two videos that had the titles Video footage of the ‘Bodoland Army’ released by Bodo Militant Group NDFB (IK Sangbijit) (Video 1) posted in January 2014 and Bodoland Army Video Song (Exclusive) A GA Production (Video 2) posted in December 2013.[17] Both the videos have been viewed more than hundred and fifty thousand times in total. The aesthetics of both the videos are similar as they show people in military uniforms with each having a separate Bodo song as the soundtrack. The videos are in low resolution and have used hand-held camerawork. Video 1 opens with a message saying that the video was released to the media by the Bodo militant group NDFB(S). The video shows men in military uniforms walking in an open green field. It shows shots of them going somewhere in a file carrying different kinds of arms and weapons. The Bodo song, which is non-diegetic and has been added during post-production, has an upbeat tempo where the female singer is singing about men who have come looking for wives and love. In the comments section, there are comments discussing freedom, criminals, innocents being killed and the giving up of arms.

Video 2, while similar in its aesthetics with the first one, is different as it shows two groups in military attire in combat. The video begins with a credit scene and shifts to the staging of the combat between two groups. The video shows that the army has a youth (presumably a Bodo militant) in custody in handcuffs who they are taking away as he is being dragged and beaten, see fig. 5. The video jarringly shifts to the scene with the army ambushing the Bodo militants in their base camp in the village. The physical features of the army and militants are different as there is racial profiling at play. Some of the army jawans are darker while the militants have oriental features as can be gleaned in the close-up shots. The setting is between open green fields and a village with bamboo and mud structures as the two groups engage in combat with each other in this landscape. In the soundtrack, the male singer begins with the word tabwbai, which means to be left behind or someone who stayed back. The singer is reminiscing an incident over his failure where he had to leave his friend behind in the hills. He remembers the blood stains of his dying friend who told him to run away and inform the news of his death to his family. The song is a lament over a dead friend who the singer failed to save.

Fig. 5. A Manipuri ‘digital’ film passed off as the Bodo army/militant group. See Ansuma Trailer- AnsumaBasumatary. “Bodoland Army Video Song (Exclusive) A GA Production.” Online video clip. YoutTube. YouTube, 23 Dec. 2013. Web. 27 Jan. 2016.

Fig. 5. A Manipuri ‘digital’ film passed off as the Bodo army/militant group. See Ansuma Trailer- AnsumaBasumatary. “Bodoland Army Video Song (Exclusive) A GA Production.” Online video clip. YoutTube. YouTube, 23 Dec. 2013. Web. 27 Jan. 2016.

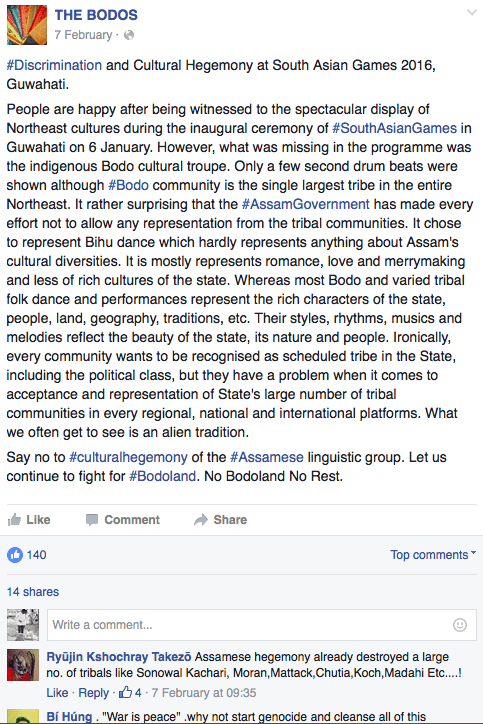

Both the videos project a sense of Bodo identity and loyalty towards one’s community; it aims to propagate patriotism towards the Bodos and the movement for the state of Bodoland. Interestingly, it is pointed out in the comment section of Video 2 that the video is taken from a Manipuri VCD film called Wanted Linthoi (2013), see fig. 6. This is a popular Manipuri film directed by Rajen Leishangthem. The plot of the film follows the story of a girl named Linthoi whose boyfriend gets picked up by the police. In her distress, she decides to commit suicide and in the attempt, she encounters an underground militant group who takes her in after which she becomes a member of the group.[18]

Fig. 6. The VCD cover of the Manipuri film Wanted Linthoi (2013).

Fig. 6. The VCD cover of the Manipuri film Wanted Linthoi (2013).

The presumed Bodo militant youth turns out to be the boyfriend of Linthoi, and the story is quite different from what it appears to be. If one were to just watch Video 2 without knowing that it is an edited clip of a Manipuri film, viewers may assume it may be a ‘real’ clip of Bodo militants in combat as some have believed it to be so, as it can be seen in the comments section of the video. The hand-held camera work, the editing, the low resolution image and narrative provides a realistic effect. However when it is discovered that it is from a film, it complicates the authenticity of not just Video 2 but Video 1 as well since both are rather similar in their appearance and aesthetics. Moreover, what does it mean to use a Manipuri film to pass off as actual footage of Bodo militants and to evoke an imagination of a Bodoland army? Their can be parallels drawn between the Bodoland movement and Manipur’s recent history of the army’s excesses and the backlash against the implementation of the notorious Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 1958. It shows the way in which the digital image can be easily morphed into representing another narrative or reality. It also begins to take charge of additional or other meanings as it begins to combine the image to take on specific markers of a certain group of people. In this example, the titling of the video, the bodies, the clothes, the landscape and the song that viewer experiences through the screen and the interface, makes it ‘real’ and highlights how there is a Bodo army which looks a particular way, carries certain kinds of weapons, the cause that they are fighting for and the message it communicates. It breaks the barrier between mediums such as news channels and official representatives that provide filtered narratives and images. Social media has been able to break away from this with the rise of citizen journalists but at the same time, the amount of content and information that is available today unprecedented. In the maze and mess of ever-growing information today, and at the speed at which movements gain and lose momentum, it has become a daunting task to disentangle the webs of networks and meaning that goes into the creation of identities and ideologies.

Today, the violent and unsettling political scenario in Bodoland and of the Bodo people is a limited narrative as things have become more complex after the arrival and proliferation of media and digital technologies that have foregrounded other realities and aspirations. Apart from Facebook and YouTube, there are Twitter handles like Bodoland Post and Bodoland News Live that informs their followers on the developments in BTC, but these accounts are not very active. On searching further on Google, posts by users on Twitter and Instagram with the #bodoland showed up. Numerous pictures of people, open green spaces, food, girls wearing ethnic wear, boys on bikes and musical instruments appeared.[19] It clearly poses a more complex network of the political, the social and the cultural that make up imaginations of identities that intersect symbolically with many other markers of meaning and knowledge. To understand these ideas and processes further, my next post would be an exploration of the Bodo films, music videos and cultural content that are circulating online via social media.

Notes:

[1] Telephonic interview with Mrs. Nagra, who has worked in Bodo films, on 8 May, 2016.

[2] See, Dutta, Anwesha. “The Politics of Complexity in Bodoland: The Interplay of Contentious Politics, the Production of Collective Identities and Elections in Assam.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. South Asia. 17. April. 2016. Web. 04. May. 2016.

[3] See, Misra, Udayon. “Bodoland: The Burden of History.” Economic and Political Weekly XLVII.37 (2012): 36-42. PDF File.

[4] See, Vandekerckhove, Nel and Bert Suykens. “‘The Liberation of Bodoland’: Tea, Forestry and Tribal Entrapment in Western Assam.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. South Asia. 31.3 (2008): 450-471. PDF file.

[5] See, Dutta, Anwesha. “The Politics of Complexity in Bodoland: The Interplay of Contentious Politics, the Production of Collective Identities and Elections in Assam.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. South Asia. 17. April. 2016. Web. 04. May. 2016.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Today the NDFB has split into many factions.

[9] Subasri Krishnan’s documentary film, What the Field Remembers (2015), is about the Nellie Massacre in Assam in 1983. In one of the worst such cases, about 2000 Muslim people were killed as a fallout of the anti-Muslim and anti-foreigner movement led by the AASU in the 1970-80s. See Ramnath, Nandini. “32 Years after Nellie, a Documentary finds Sorrow, Indifference, and a Refusal to Forget.” Scroll.in. Scroll. 16. July. 2015. Web. 06. May. 2016.

[10] See footnote 2.

[11] See the works of Internet and media theorist, Geert Lovink like Networks without a Cause (2011), Unlike Us Reader (2013), Social Media Abyss, Critical Internet Culture and the Force of Negation (2016) and others. He has extensively critiqued the Internet, social media and technology that, unlike the initial hey-days, are now in the control of governments and big corporations for the way in which they are shaping the contemporary world and life on an everyday basis.

[12] The Zapatistas belong to various ethnic groups who are mainly peasants. See the section on Zapatistas in Chapter 2, The Other Face of the Earth: Social Movements against the New Global Order, from Castells, Manuel. The Power of Identity. Vol. 2. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2010. PDF file.

[13] There are also blogs like The Password or The Bodo Tribe ‘Online Magazine’, that focus on news, information and issues of Bodo (tribal) people and the BTC region.

[14] There are local newspaper like Bodoland Guardian and Ingkong.

[15] The Bodo language is officially written in the Devanagari script today. It is believed that their original script was Deodhai which is lost today.

[16] NDFB(S) is faction of the NDFB(R) which split from the erstwhile NDFB.

[17] I will refer to them as Video 1 and Video 2 for the sake of convenience. They are posted on YouTube by different users.

[18] It was released in Imphal and because of its success, Wanted Linthoi 2 (2015) was made later. For a discussion of Manipuri VCD (digital) films, see Yumnam, Ranjan. (2007). Imphalwood: Digital Revolution and Death of Cinema. Sarai Independent Fellowship Project 2007. Sarai. 24. March. 2007. Web. 30. April. 2016.

[19] See Twitter and Instagram for the pictures with the #bodoland.