This is the third research note by Ankush Bhuyan, one of the researchers who received the Social Media Research grant for 2016.

This is the second part of my two-part exploration of the Bodo community and its engagement with social media and the online world. This post builds on the first part where the focus of investigation was on the insurgency and the presence of reports, pictures, discussions, videos on social media pertaining to this.[1] This post will explore the presence of Bodo entertainment content, VCD films and music videos on websites like YouTube, and shared via social media. The focus will be on the kind of content that is shared as well as on specific content, exploring the links and connections that go into the production of a Bodo identity through the medium of the Internet, and the ways in which media today aids in the scattered explosion of such ideas and beliefs. This post will seek to give a brief overview of how online content foregrounds a sense of Bodo identity and Bodoland, leading up to my next post which will be an analysis of the complex ways in which the political, social and cultural operate in the digital and social media landscape of the Bodos.

Fig. 1. A Bodo couple welcoming to The Great Bodoland Facebook page. See The Great Bodoland. “Bodo-Assam.” Facebook. Facebook. 30 June. 2016. Web. 2 July. 2016.

Bodo Culutral Content

There are numerous Facebook pages catering to different aspects of Bodo identity and culture.[2] The posts have text and images that are intrinsically linked to Bodo identity. Even though there might not be many shares, likes or comments in all such posts, one can notice that, apart from the usual appreciative comments and likes, some posts draw much more attention than others depending on the nature of the content.

Fig. 2. A screenshot of Bodo Cuisine’s post on the recipe of Curry of Taro Stolon. See Bodo Cuisine. “Thaso Aithing wngkhree.” Facebook. Facebook. 02 July. 2016. Web. 06 July. 2016.

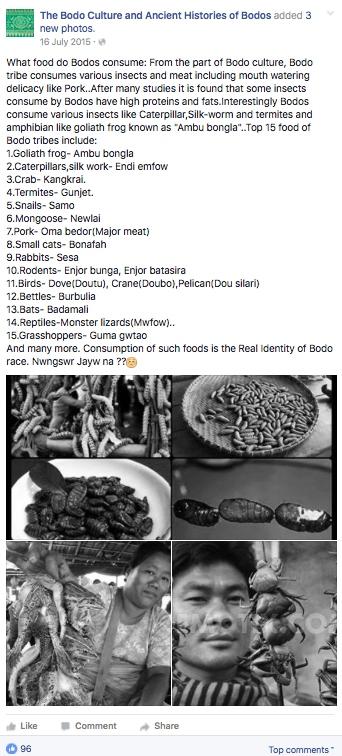

Fig. 3. A Facebook post of what Bodo people consume from The Bodo Culture and Ancient Histories of Bodos. See The Bodo Culture and Ancient Histories of Bodos. “What do Bodos consume.” Facebook. Facebook. 16 July. 2015. Web. 29 June. 2016.

One such Facebook page, Bodo Cuisine, focuses on Bodo food. The page from time to time posts pictures and recipes of traditional Bodo dishes and types of food Bodo people consume with pictures of the dish along with the ingredients’ names in Bodo, Assamese and English, and the recipe. Such posts draw a lot of attention and comments not only because of the detailed and easy-to-read text but also because of the aesthetically captured images of the dishes that heighten the senses, fig. 2. Another Facebook page called The Bodo Culture and Ancient Histories of Bodo has a post that informs its followers what Bodo people consume. However, this has to be read critically as it aims to provide a distinct culinary experience that is rooted with being Bodo, regardless of whether all Bodo people consume the type of food mentioned in the list, fig. 3. The post even says that “Consumption of such foods is the Real identity of Bodo race” (sic).

Bodo songs and music videos from YouTube are frequently shared on some of these Facebook pages as well. A Facebook page called All bodo film focuses on information related to upcoming Bodo films by posting trailers that are linked to YouTube. The page also promotes distributors, production houses and actors. Apart from promotions, they also work as distributors. On the page, Bodo actor Shimang has been mentioned multiple times alongside his pictures and the names of movies he has starred in. Additionally, production and film studios have their own Facebook pages and YouTube Channels like Alari Multimedia, which posts photos of its studio and the kind of production work they do. They post photos from sets and locations which serves as a making of the film or music video. Most of the pictures’ focus is on the cameraman and the camera. Another similar Facebook page, Lwihwr Recording Studio, promotes local artists and shares songs and music videos from YouTube.

I have noticed that among the Facebook pages that focus on Bodo identity and Bodoland, there are recurring images of the landscape, Bodo ethnic clothing (Dokhona), folk dance (Bagurumba) along with music videos and film trailers which are shared online. Moreover, social media has also become important to spread news about events such as the annual Bodo Rock Clash, Annual Conference of All Bodo Students’s Union, the fashion show called Dokhona,[3] some of which have their own dedicated Facebook (event) pages as well, fig. 4.[4]

Fig. 4. Dokhona fashion show’s social media invite. See THE BODOS. “Dokhona- a glimpse of the golden motif.” Facebook. Facebook. 26 April. 2016. Web. 15 June. 2016.

A search on YouTube reveals that there are innumerable results for Bodo songs and music videos. However, it is unclear whether they are from films or music videos unless the titling of the video makes it clear. Moreover, it is ambiguous because most of these are posted by users but on a closer glance it can be discerned that the production value of the music videos are better than the ones from the films. Also, music videos are posted by the artist themselves and by production houses. Music videos are far easier to produce because of the lower cost of investment and with the rise of popular video hosting sites such as YouTube, the way to exhibit them has also become easier. YouTube is one of the ways to showcase musical talents and products for popular consumption but it usually works in combination with stage (live) performances for greater visibility and recognition.

Live performance shows by Bodo artists seem to be part of this new feedback loop. Cultural shows during festivals of the harvest season are big crowd pullers at the local level which showcase local talent in the form of singing festive songs to folk dances in traditional/ethnic attire. Now there is the Bodo Rock Clash concert that has further helped local rock bands and artists to make a name for themselves as was the case with Nwjwr, Lwihwr, and Daohang. Moreover, stage performances at fashion and award shows are also on the rise as such events become more commonplace. The popular Bodo singer Anaya Brahma, for instance, has a number of music videos on her YouTube channel and has a considerable following on her Facebook page, fig. 5. She performs in shows, awards functions and participates in events very much in the same vocabulary as celebrities from Bollywood and other mainstream film industries. Brahma must be one of the few well known Bodo people who has managed to crossover to Hindi music and perform across the country in places like Kolkata, Mumbai and Delhi. Brahma talks about her community on stage and wears the traditional Bodo attire, the Dokhona. This could provide access and opportunities for artists to increase their brand value and also represent their community as they travel and work in other industries and places.

Fig. 5. Anaya Brahma’s Facebook fan page. See Anaya Brahma. “Anaya Brahma” Facebook. Facebook. Web. 2 June. 2016.

Local artists and singers have the opportunity to showcase their talent through these events that help them come closer to their listeners. Richard Dyer has argued that stars are products of multiple media platforms and practices, where the public does not know them personally but through the media.[5] However, Ishita Tiwary in her study of the local star in Malegaon has pointed out that this phenomenon is linked to the community as the actors are from the same region.[6] There is thus a possible convergence of Dyer’s and Tiwary’s arguments as Bodo singers who have dedicated YouTube channels provide contact details for events and live performances.

A Selection of Bodo Clips in Circulation

Film clips are harder to read because they tend to become independent from the films because of the loss of context from which it has been sourced from. The clip or scene becomes a standalone source of aesthetic and narrative information. There are clips posted but they are divorced from the larger narrative and the identity of the film as sometimes it is not even mentioned from which film the scene is taken from as they are titled as vaguely as ‘Bodo film’. However, their might be more details which tell you the name of the film and the cast. For example, in a fight scene posted by the actor from the scene itself, from the Bodo film Khither, the three minute clip shows one man fighting a group of men in an open area. It shows the man, presumably injured as he holds a crutch, engaging in combat with the group of men attacking him. The fight scene is fairly sketchy but the user has not posted it for comic relief unlike some others who post fight scenes from Assamese films such as the one starring the infamous Rajkumar who directs, produces and acts in his own films such as Terrorists Enter My Home. These videos are titled by users as Worst Assamese fight scene ever, FUNNIEST ASSAMESE FIGHT SCENE, etc. The fight scene from Khither takes on a different dimension than these because it is posted not for its poor aesthetic value or comic elements but for its action and drama. The scene shows a moment of intense encounter with heightened guttural shouts and slow motion editing and bodies flying around in a grass field as cows lazily continue to graze on the field in the background. It provides a sense of the everyday mixed with the extraordinary as the injured hero beats up his assailants. Moreover, the tragic part is that he does not survive as towards the end of the clip he is badly injured and shot with a gun as blood graphically erupts out from his body, fig. 6.

Fig. 6. The fight scene from the film Khither uploaded by the actor Bhupen Rb on to his channel. See Bhupen Rb. “KHITEHR Fight (Bodo Film) – Bhupen Rb”. Facebook. Facebook. 19 December. 2013. Web. 2 June. 2016.

A music video called Gwjou Rwkha Nuthai (Clear Vision for Ahead) made by a group of students from Assam University, Silchar is about human rights (Subung Mwnthai in Bodo) as it clearly spells it out in the opening credits and is dedicated to innocent Bodo people who have lost their lives in the hands of security forces, fig. 7. The song raises questions on the killing of Bodo people and youth without any court of law administering justice. The group of boys sings about aspirations, family, love and peace juxtaposed with the mindless destruction of Bodo dreams and hopes. As the boys sing and dance, a Bodo youth and another male family member (his father or elder brother) are killed by security forces in their courtyard just as the boy is leaving the village for his university. Later the women of the house cry over their dead bodies when they discover them lying sprawled on the ground. The video showcases more dead bodies of men lying scattered on the ground with cross cutting with scenes of the singers moving around on similar landscape wearing ethnic Bodo and western clothes. The song projects the atrocities on Bodo people from the point of human rights but the group of men also borrow from the boy band aesthetic as they dance and move in choreographed formations. The song and the video positions itself to be an anthem with its crescendos and young men and women in ethnic Bodo attire holding hands in a line and marching towards a better future.

Fig. 7. A screenshot from the music video by Assam University students. See Ramtanu Brahma. “Subung Mwnthai- HD सुबुं मोन्थाय – गोजौ रोखा नुथाय.” Facebook. Facebook. 2 March. 2016. Web. 2 June. 2016.

A music video by Preeti Swargiary called Bodogami (Bodo Village) is about Bodo villages which are filled with happiness and joy. She sings about the open fields and the Bwisagu season (festival of harvest) with the hope that the misery is no more. She also mentions the Budang haluaa (Budang farmer), who goes to the fields to till the land for Jwsa and Maibra rice. The video completely focuses on Bodo identity through the life of Bodo people in villages. The video showcases the verdant landscape with farmers working on their lands, women weaving clothes and working in their houses which is juxtaposed with Bodo girls performing the Bagurumba folk dance. The video also shows village life as people gather in the evening around a fire to eat, play instruments like the flute, sing and dance. The singer Preeti Swargiary plays the lead in the video as she sings and dances in the video. In traditional Bagurumba performances, there are no lead dancers as the women stand in a line or in rows and columns as they dance wearing the Dokhona. However in this video, the singer is placed prominently not just by her placement which makes her the central figure in the dance sequence, but also through her differently coloured Dokhona in comparison to those of the background dancers, fig. 8. Moreover, the narrative is also about love as she yearns for her lover who appears wearing ethnic Bodo clothing. This insertion of the singer as the lead not only aligns the visual with the music video aesthetic and not just a song and dance sequence that showcases culture and tradition. It foregrounds community life as well as individual identity in tandem with a larger set of common beliefs.

Another music video by Anaya Brahma called Swrziw Ang Dinwi (I Create Today) is about a woman returning to her village and the video focuses on the journey. Brahma sings about the desire to transform with nature and Agor (the embroidered designs on the Bodo clothes). She also mentions about the green villages, the river that flows beside it and the sound of Kham, Sifung and Serja (musical instruments) that she can hear. She adds that it is her heart’s prayer and poem to serve the community. The video focuses on the singer’s cultural identification with her homeland which is to do with cultivated green fields, men playing musical instruments used in Bodo folk music, and traditional garments. The singer is wearing fashionable western clothes but when she reaches her village, she is welcomed and she changes into the Dokhona and participates in the Bagurumba dance. Similarly, her Dokhona is different from the other women and she is placed centrally. The end credits of the song mentions it as a “Bodo Modern Song” (sic) which is an interesting positioning of the music video, the song, the aesthetic of the video and the singer herself. It positions modernity as not in opposition to tradition but as the traditional which has been appropriated and co-opted into the modern life. Brahma’s narrative depicts the smooth transitioning into the traditional life that apparently exists in the village, while where she comes from, the city, can be deduced from the Ford Fiesta that is taking her to the village with the number plate visible in one shot that tells us that car is registered in Guwahati. This “Bodo Modern Song” might indicate the non-conflicting nature of the traditional and the modern. However, it stereotypically identifies village life with the traditional and leaves us with a sense of its ahistorical nature without taking into consideration how rural life and areas have also transitioned over the decades.

Other Bodo music videos by popular singers like Bitu Narzary and others are love songs where either the boy and girl are professing their love for each other in splendid vistas, or the boy and girl are wooing each other. There are also videos of cover songs of Bodo songs, and a Bodo heavy metal rock band by the name of Lwihwr has received recognition from MTV for its music. One of the most interesting Bodo bands is Nwjwr which makes empowering rap songs in English that talk of dreams, aspirations and happiness. In their song Underdog Cries the two artist rap stanzas in an open green field under a slight drizzle and soft lighting. The video is an example of the representation of many aspirations of people and not just Bodo youth but young people who want to follow their dreams and passions that do not necessarily talk about identity politics but focuses on delivering a universal message. The use of the english language and the rap form is also indicative of the acute awareness of a global audience and the desire and aspiration for wider appeal and connect.

Towards an understanding of the Bodo Online World

The dynamic and vibrant presence of Bodo content in the digital world and social networking sites is evident from my overview of Bodo political and cultural content in this two-part post. At first glance the complex interplay of such content with the larger socio-political situation of the Bodos, their homeland and identity seems to be scattered and unclear. However, it is possible to explore and analyse some of the ways in which the online and digital world play an integral role in the newer ways in which both the political movement as well as the mobilisation of Bodo people and youth happen in the contemporary. The next post will seek to analyse such relationships and look at how the Bodo identity finds itself expressed at the crossroads of the political, social and cultural in the online world.

Notes:

[1] For the first post, see Bhuyan, Ankush. The Quest for Bodoland: Social Media in the Time of a Separatist Movement – Part One. Sarai. Sarai. 02 June. 2016. Web. 02 June. 2016.

[2] I have mentioned some of the Facebook pages in my previous post such as THE BODOS but there are numerous more like the The Bodoland Monitor, Bodoland Today, Bodoland Sansri, The Great Bodoland, etc.

[3] The Dokhona has a special place and significance for the Bodo people as it is one of the most culturally identifiable clothing of the Bodo women, along with the Bagurumba folk dance. The Dokhona in particular is also a hashtag on Instagram where images of girls wearing the traditional garment are posing in front of the camera. On scrolling throught he pictures, most of the pictures are taken with the women posing for the camera flaunting the dress at either in some occasion or casually.

[4] Bodo Rock Clash concert’s Facebook page and Dokhona fashion show’s Facebook page.

[5] See, Dyer, Richard. Stars. London: British Film Institute, 1979. Print.

[6] See, Tiwary, Ishita. “The Discreet Charm of Local Practices: Malegaon and the Politics of Locality.” BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies 6.1 (2015): 67-87. PDF file.