In this post, Vibhushan Subba, one of the researchers who received the Social Media Research grant for 2016, introduces his proposed work.

What is a ghost?

A tragedy condemned to repeat itself time and again? An instant of pain, perhaps.

Something dead which seems to be alive.

An emotion suspended in time.

Like a blurred photograph.

Like an insect trapped in amber.

– The Devil’s Backbone (2001, Guillermo Del Toro)

Picture first, in the murky blue of the sylvan night, one of the vampire’s minions in white satin with exaggerated face paint, false teeth and styrofoam wings flickers in front of you. She struggles to maintain her balance and as she is wheeled towards the camera her wings keep disappearing from shot to shot. Strangely though the disappearing wings seem to have little effect on the vampire’s flying skills. This haunting image is from Harinam Singh’s Shaitani Dracula (2003) which has become iconic in “B” cinephile circles. Sure, it may just be flawed continuity or men in cheap skeleton suits stomping around scaring unsuspecting victims from behind the bushes. It could possibly be the joy of watching a victim scaring off a monster with an unconventional crucifix, a wheel spanner in the case of Bhoot Hi Bhoot (2000)[1] or it could be the witty dialogue of the Bashir Babbar[2] variety but what is more fascinating is the sudden explosion of a cinephilic desire for such low genres which has exploded on the internet and how it is being circulated.

Figure 1: Airborne with the wings, Shaitani Dracula

Figure 2: Airborne without the wings, Shaitani Dracula

Consider this, Aditya Savnal, a blogger and content writer, in his post The Ootywood series – Loha feels that Martin Scorcese drew inspiration from Loha while filming The Departed. He believes that Mark Wahlberg’s character borrows heavily from Inspector Kale’s character in Loha. Meanwhile, the high priest of sexploitation, Kanti Shah has been catapulted to cult stardom. His film Gunda (1998) is the stuff of legends, receiving a rating of a perfect 10 in IMDB [3] at one point of time, unsettling films like The Godfather and The Shawshank Redemption. In other platforms DVD labels are competing against each other to upload their most obscure collections. Elsewhere, award shows are being organised to showcase the worst in cinematic history (Golden Kela Awards comes to mind) [4]. In other words it would be no exaggeration to state that there is today a vibrant community of B-movie cinephiles which I call cinephilia undead operating within the folds of the internet. Born completely on the networked environment of the internet, this cinephilia has revived the forgotten history and aesthetic of B-movies, horror and sexploitation films that sit at the bottom of the cinematic ecology in India. “We watch everything that these movies have to offer…say for instance if an audience member has a fetish about watching people having sex with ghosts, they will show that. Where would you get this in normal Bollywood? We are the people who watch these kinds of films and we are on YouTube, Twitter, FB, blogs…”,[5] says Aseem Chandaver who is one of the most active B-film enthusiasts and collectors operating on the net under his pseudonym Neelouli on YouTube and Gina Kholkar on Twitter. He started his YouTube channel Neelouli in February 2007.

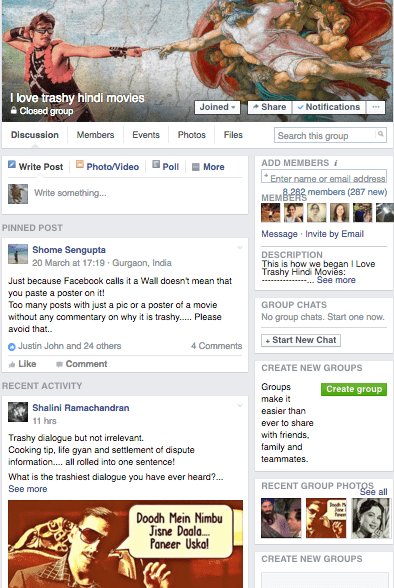

From being ridiculed and put down as trash these films are today openly celebrated on internet forums, movie blogs, YouTube channels, Facebook and Twitter pages. The Facebook page I LOVE TRASHY HINDI MOVIES, for instance, which has more than 5000 members is an eclectic collection of film clips, film posters, gifs, memes, music recordings, old photographs related to B movies. The contributors to this page range from filmmakers, copywriters, bankers, engineers, research scholars, chartered accountants and students marks the rise of a new class of people that have started to watch these films.

Figure 3: Facebook Page I love trashy hindi movies

This project seeks entry into a “B” moment at the twilight of its existence. With the speedy folding of single screen theatres and shrinking exhibition spaces there was a feeling that the B-movie was headed towards a slow demise even in the circuits that it travelled in. It was in this period of uncertainty that a wave of cinephilic B-movie desire erupted across social media platforms that refused to let it slip into oblivion. It is this activity I propose to track and I begin by acknowledging this new community and the kind of activity I have mentioned above and hope to explore further by investigating the creation, nature and evolution of this cinephilia -which has produced a mobile and alternative archive – in order to understand the altered relationship between the producers of content and digital technology and stage a debate around censorship, ownership and alternative histories. For, it is only true that to a large extent what becomes part of cultural memory depends on the circulation of carefully constructed canons and archiving of cultural works that are considered to be part of the official history. But what of those outside the canon, the official archives and beyond the official history? Lurking beyond the official narratives are degraded, discarded and forgotten cultural objects like an emotion suspended in time. In this project, I propose to track the rise of a cinephilia centered around the obscure, the obscene, the feared and the forgotten.

Investigating this new cinephilia will help us unpack the regimes of cultural memory, the repackaging of a marginalised past, its growing popularity and the need for new ways of analysing screen cultures outside the mainstream. While operating these online channels, the owners not only collect content but also modify them to suit public temperatures. Thomas Elsaesser says re-mastering is “the sense of seizing the initiative, of re-appropriating the means of someone else’s presumed mastery over your emotions, over your libidinal economy, by turning the images around, making them mean something for you and your community”.[6] The re-mastering of clips on YouTube is an example of a new found power to re-arrange, re-appropriate and re-imagine images to suit channels and a fetish to play with the text digitally, altering its meanings and effect upon the viewers.

In investigating this cinephilia and its growing presence on the internet I am not only interested in what was forgotten but more importantly in why it is being remembered now and how repetition through social media becomes a form of dissemination. Being condemned to repeat itself time and again is no longer a tragedy but a powerful means of gaining visibility.

Notes:

[1] Boss (2000). Bhoot Hi Bhoot [Motion Picture]. India.

[2] Bashir Babbar was a director, producer and writer known for the dialogues in films like Gunda.

[3] This was largely due to a boosting campaign undertaken by students across IIT’s (Indian Institute of Technology) in India starting in 2003.

[4] The Golden Raspberry Awards also known as the Razzies is an award ceremony celebrating the worst in Hollywood filmmaking with award categories like ‘worst actor’, ‘worst director’, ‘worst screenplay’ amongst others. Started by copywriter and publicist John J.B. Wilson in the 1980s it is held every year a day ahead of the Academy Awards. The name is derived from the phrase ‘blowing a raspberry’ which is a derisive way of making a flatulent sound. Inspired by the Razzies The Golden Kela Award recognizes the worst in Hindi cinema and was started by Random Magazine in 2009.

[5] Chandaver, Aseem. Personal Interview. 11 April 2014, Matunga Road, Mumbai.

[6] Elsaesser, Thomas. “Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment.” Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory. Eds. Marijke De Valck and Malte Hagener. Amsterdam:Amsterdam University Press, 2005. 27-44. Print.