This is the third research note from Charu Maithani, one of the short-term social media research fellows at The Sarai Programme.

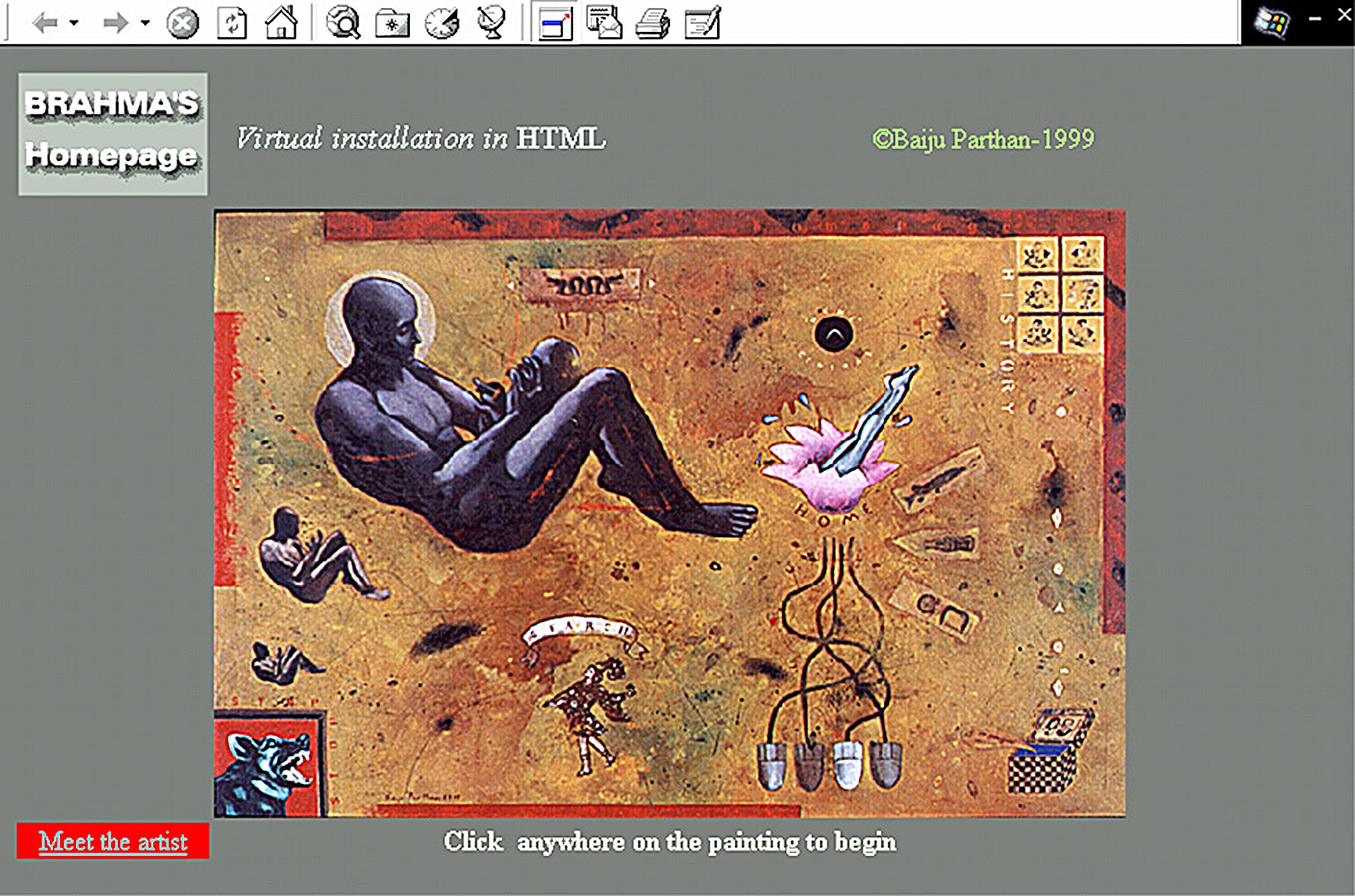

In 1999, Baiju Parthan paid serious attention to the changes that were slowly taking place with the novelty of the internet. The next advancement since industrial revolution, the world wide web was becoming a reality. Computers were getting as common as television. Our understanding of the world and relationships was changing. It was around this time that Parthan made one of the first interactive digital work in India. It was called Brahma’s Homepage.

Brahma’s Homepage had two aspects – a painting on the wall, and the same painting on a computer screen. Through this work, Parthan attempted to draw a parallel between the physical and the virtual. Various parts of the image were hyperlinks, clicking on them revealed different stories. Just as the painting on the wall can be decoded/read through its icons and metaphors, the painting on the computer revealed meanings and narratives. Parthan created a fictional narrative of incidents inspired from his life along with a brief history of painting, as hyperlinks. Referring to Brahma, the creator of the world, Parthan wondered what would Brahma’s webpage look like and attempted to answer it in the artwork giving a historical reference to the art of image-making.

Brahma’s Homepage was a simple HTML program created by Parthan himself and was run on Internet Explorer. Parthan being trained as a painter, is used to doing all the work himself, even if it means learning new skills like computer program coding.[1] With available tools on the computer, he wanted to explore if computer can be included in visual arts and learnt HTML to be able to code. The similar sensibility of embedding hyperlinks in webpages can be seen in his other works created around the same time like Necessary Illusions with 24 cups of Coffee (2000).

Code, created in 2000, is one of Parthan’s most successful digital interactive work. This work allows the audience to ask questions to the computer that answers from the I Ching database. Made on HTML, Java and JavaScript by Parthan and run on Internet Explorer, Code is presented as an art installation. This work also displays the code for the viewers to see. A basic algorithm based on randomization answers the question from I Ching. The answers are fairly open-ended that the audience can easily contextualise with the question, thus surprising the audience with its prophetic vision. A synthetic persona in form of a face is also present – a simple gif that smiles when clicked on.

This work is significant as it is probably the first artistic project to explore the digital presence. Subsequent to this work, Parthan established his practice in digital interactive installation and interrogated the idea of cyborg and virtual identity in his projects like A Diary of the Inner Cyborg (Asystole- Disrupting the Flow) (2001-2002), showing at London, Vienna, Glasgow and Tokyo.

It will be interesting to see if works by Parthan can be presented as websites or can be made available as downloads. It would then truly take the form of a net art project. For Parthan it was a conscious decision to not disseminate them so easily in order to maintain their identity as artworks. “The aura of the artwork needs to be protected”, he says.[2]

Artists’ engage with techniques of image making to express meaning. This leads them to explore multiple medium. Parthan is an artist and is continuously looking for different forms; digital images were his medium for a long time before he moved onto other ways of expression. The pressures of keeping up with programming language and technical update drew him back. He is currently working with lenticular printing.

—–

In 1999, another artist Kiran Subbaiah, based out of Bengaluru, was delving into net art. His first project Netscape Escape , and probably the first net art project in India, was a network of chances that leads to the same end. It was a flash program, made by Subbaiah himself, whereby he narrates a story to the audience and presents them with choices each time. The audience chooses the way in which the story progresses. They have an illusion of choice as no matter what is chosen the end is the same every time. This program still runs on Windows 98 version, but the computer screen sizes that are currently used are not suitable. When he made this work in 1999, the screen sizes were completely different – they were 4:3 and 800 X 600 pixels, as compared to 16:9 and more than 1024 X 768 pixels that we have in desktop nowadays.

Subbaiah did a few flash based projects, but his interest was in creating pseudo virus programs. He made Crash Run (2001-02) using existing programs. Like a 1990s mixed tape, he created a few programs as one compilation which when played would wreck havoc on the screen of the user. This program automatically deteriorated the screen. The computer seemed to crash uncontrollably. But it was just a simulation of the crash provided by the program, the system was otherwise secure. The program had to be uninstalled to be able to use the computer normally. This program can be downloaded from Rhizome and Subbaiah’s website. The latter does not exits since the shutting down of geocities. One can still run the program on the Windows 98 OS.

Another program that Subbaiah wrote from scratch was Use_Me in 2003. Unlike Crash Run, this program has to be run by the user. It is dependent on the user’s interaction. If the user does not interact, it remains unobtrusive. Once it is run, the user has to interact with actions like clicking, typing, which leads to different result. It is like a game from which the user cannot get out easily. A certain combination of keys has to be used to get out of the program.

Subbaiah’s was drawn to net art as it offered new possibilities and an opportunity to connect to people. In my recent conversation with him, he points to the fact that in the late 1990s, his early years as an artist, there was a lot of emphasis on Indian art. He wanted to escape this and started exploring internet as a medium not only for communicating with an audience, but also to share ideas and learning. Back in the day internet, according to Subbaiah was very liberating, not unlike today when it has become like television – too much noise and less access to what one wants. [3] Subbaiah also points out to another frustration with technology – it gets too old too soon. Unless one is a digital technologist, we can’t really predict the technology that evolves fast, rendering many tools obsolete too soon. This is not encouraging for Subbaiah as he thinks art should last long. He chooses the emphasis on longevity that is provided by other medium such as video and sculpture, instead of works that are left only as documentation.

—–

In early 2000, Prayas Abhinav was distributing his e-publication, Crimson Feet, through email lists. These lists were created by compiling email addresses from all over the world wide web. Equivalent to spamming people, between 2001 and 2004, Prayas sent 6 online editions of Crimson Feet to an audience that never signed up for it. In my conversation with him, he explained the process of getting the email addresses by sending spiders to various web pages. Crimson Feet contained English poetry and fiction, and was built on Dreamweaver for sometime before Abhinav shifted to Spip.[4] By 2006, Abhinav stopped renewing the the domain leading to the end of Crimson Feet.

In 1999 – 2000, Abhinav opened a website called Stinksite. He published his writings on this site. At a time when blogs had not yet emerged, Abhinav used static webpages for writing, which were given as hyperlinks on the homepage. Stink site was built on HTML (Microsoft Frontpage) and lasted only till 2001.

Soon Prayas Abhinav started exploring content management systems. With easy access to server space (his brother had a server) he immersed himself in developing web architecture. Zope, a content management framework and Plone, a content management system, were his major areas of attention 2004 onwards. Concerned with open source software and free content distribution, Abhinav’s exposure increased by visiting conferences such as Wizards of OS in Berlin in 2004. Abhinav used softwares to create online institutional structures based on ideas and functions that existed only in words and never for real. Situating ideas around temporary architectures of grandiose, but fictitious institutions.

Expanding upon this idea, Abhinav launched Museum of Vestigial Desires in 2012. Another writing based web project, Museum of Vestigial Desires attempts to define processes and concepts through language. Reflections on museums, writing, reading, cinema, conversation, play and many more, exist on this website.

Built on Kirby CMS, it seems self serving though Abhinav insists that it is a way of broadcasting experience. “When you produce an experience, you have the freedom to narrow its scope of access to alter its intensity. Intensity and access are inversely related, the more the access, the less the intensity and the less the access the more the intensity. So the freedom to narrow the scope of experiences that we produce is important. If we didn’t have that freedom, we would be compulsive mass-broadcasters.” [5] Prayas Abhinav as the museum’s co-director is available for interviews and conversation on selected days and times, details of which are published on the museum’s Facebook page.

Prayas Abhinav says that his desire to experiment led him to delve into software technologies. He points out that people did not have much choice as the content management systems were being created. The web software development relied heavily on communities of interested people who would ask, share, review and learn from each other. Mostly one doesn’t need to familiarise with the entire software, but can be task oriented learning to be effective and productive.

—–

In 1985, Jean-Francois Lyotard and Thierry Chaput curated an exhibition, Les Immateriaux, at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The exhibition took two years in the making and was the largest and most expensive exhibition till that time. The exhibition explored questions around man’s relationship with nature and other man-made objects on the arrival of new technology. New technologies, its challenges and re-articulations of relations in post-modern conditions were the areas of concern. The exhibition showed new materials including personal computers, integrated circuits, and works by Daniel Buren, Delauney, Jaques Derrida, Kasimir Malevich, Dan Graham among others. Viewing the exhibition was actually experiencing it and interacting with it. The audience members were given headphones which would catch different radio frequencies at different locations in the exhibition. Five zones were created in the exhibition — material (the support of the message), materiel (hardware that moves the message), maternity (the function of the sender), matter (what the message is about), and matrix (the code of the message).[6]

The exhibition was significant in two aspects. Firstly, it presented a new form of exhibition practice. Secondly, the exhibition is directly concerned with media practices. The second aspect is of concern to us with respect to net art practices. Many of the questions that were raised in the exhibition, phenomenon that were present behind the works, were later tackled by various artists in net art. “…Many more of the activists of telecommunications and net art period of the 1990s did not see the show or even know about it , yet they dealt with some of the same subjects; so it appears that Les Immateriaux, dug up almost instinctively, ideas that were about to surface in the arts in the following years.” [7]

Les Immateriaux is rarely contributed with being an important marker in digital art and media practices. The term ‘net art’ had not been invented and internet based communication were far from familiar. Largely, it’s presentation of the immaterial nature of media was problematic. [8] In this regard Documenta X in 1997 is credited with capturing net art in the mainstream media art practices. Net art had been brought out of its alternative existence and was noticed by museums and institutions. The net art projects in Documenta X (I have briefly written about it my previous post), can be accessed here http://www.ljudmila.org/~vuk/dx/english/frm_surf.htm. The inclusion of net art projects stemmed from the curator, Catherine David’s vision of looking beyond the spatial and temporal limitations of experience provided in object based art.

The ideas of immateriality find their true resonance in net art. “By ‘semiotizing’ the phenomena of the real world, the net opens up very specific gaps for artistic interventions…. the contradictions between the physical and real and the virtual and immaterial are not limited to net art, but have been dealt with in other, more traditional art forms, in the environment of the Internet and its technical structures, they have an even greater relevance.” [9] One structure of the digital in which relations with the immaterial is reified are software coding and programming. Softwares facilitate the creation, execution of actions and staging of their effects. The artists discussed above were able to learn HTML, Java and Flash in order to produce their work. They used software to create content and engage with their audience. It was their interface to the imagination and the world.[10]

Notes

[1] Conversation with the writer on 24th July, 2015.

[2] Conversation with the writer on 24th July, 2015.

[3] Conversation with the writer on 29th July, 2015.

[4] A collaborative publishing system for the internet http://www.spip.net/en_rubrique25.html

[5] Abhinav, Prayas, Self, 2013, accessed on 24th July,2015, http://www.museumofvestigialdesire.net/books/self

[6] Martin, Lesley, Art & Text 17, 1985, accessed on 25th July, 2015, http://csmt.uchicago.edu/annotations/greenbergthinking.htm

[7] Baumgartel, Tilman, Immaterial Material, At a Distance: Precursors to Art and Activism on the Internet, Ed Annmarie Chandler, Norie Neumark, MIT, 2005.

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Manovich, Lev, Software is the message, Journal of Visual Culture, 2014, Vol 13, Issue 1.