This is the fourth and final research note from Ritika Pant, one of the researchers who received the Social Media Research grant for 2016.

Televisual fandom is an amalgamation of multiple dimensions that include the televisual text, TV stars, corporate machineries of marketing and promotions and most importantly the fans. Fans are a significant parameter in analyzing the popularity of a television programme or a TV star; and fandom, therefore, is an important scholarly paradigm that redefines star studies on the small-screen. While the earlier forms of television-audience interactions were limited to sending letters to the broadcasters/producers, it is with the emergence of digital media, that this interaction has taken “one of the most intimate and far-reaching forms of sociability” in contemporary times (Elliott, cited in Holmes and Redmond, 2006: 3)[i]. Fans, S.V. Srinivas asserts, are often “characterized by their excess, hyperbole and even obsession” (1996:8)[ii], and this excess is evident in the fascinating fan-texts they create in the digital domain. Taking a clue from Srinivas’s study of the star-fan relationship, I will examine how the fans create a ‘virtual space’ by self-designing fan clubs in the form of fan pages on social networking sites to help promote televisual content alongside their favourite stars. I am primarily interested in examining how the internet has become a platform for the proliferation of transnational digital fandom wherein television fans, in their diverse socio-cultural backgrounds interact with transnational content and extrapolate different significations for the same content. My attempt in this post, therefore, is to understand digital fan cultures in television through an analysis of the enormous cultural production which takes place in the form of memes, spoofs, GIFs and fan-fiction, and trace important sites on the internet through which a transnational audience accesses, interacts with and creates new content and contributes to digital fandom. For the purpose of this post, however, I will limit my discussion to specific examples to elucidate how transnational and transcultural appropriations of televisual text and of the stars are multifaceted and often produce a complex collage of both the star and the text.

Transcultural Fans and Complex Star-Images

The distribution of Indian television content in the overseas market has been made possible by major transnational corporations like Viacom 18 and News Corp. having a firm hold in the Indian entertainment business. While international beaming of Indian TV shows caters to the Indian diasporic audiences in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada etc.; syndication of Hindi soaps to countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, Afghanistan and Turkey has not only made the saas-bahu banter globally popular but has also added to the stardom of small-screen stars. Along with media content that transcends national boundaries, the figure of the ‘star’ becomes a driving force through which such transnational circulations are made possible. A recent article in a national newspaper discussed how both Hindi soap operas and their stars have gained global fame in countries like Egypt, Afghanistan, United Kingdom, Turkey etc. While the soap opera actress Mandira Bedi is still known as Shanti in Sri Lanka, actors Sanaya Irani and Barun Sobti of the soap opera Iss Pyar Ko Kya Naam Doon (IPKKND) have a huge fan base in Turkey, where the show is aired in Turkish language[iii].

IPKKND is a popular Hindi soap that aired in India on the Hindi General Entertainment Channel Star Plus from June, 2011 to November, 2012. During its telecast the show recorded ground-breaking ratings and actors Irani and Sobti achieved immense popularity through their fictional characters Khushi and Arnav respectively. The soap opera has been dubbed in numerous regional as well as foreign languages and has inspired many international remakes[iv]. This year the show was telecast in Turkey as Bir Garip Ask (A Strange Love) and was well received by the Turkish audiences. The success of the show and the popularity of its actors can be observed in social networking sites where IPKKND fans have created Facebook fan pages, Instagram accounts and YouTube channels to promote their favourite show and its stars. For instance fan pages like Sanya Irani Team Turkey, Barun Sobti Turkiye Fan, Bir Garip Ask Dizisi are a few names that top the search results on Facebook. Similarly, Bir Garip Ask Fan and Arnav & Khushi IPKKND Turkey are some channels that regularly share audio-visual content on YouTube. The posts/content shared on these sites range(s) from main text that includes short video clips or pictures form specific episodes of the show to extra-textual material like behind the scenes footage, interviews of the actors, personal photographs of the stars and video clips of other shows done by the actors[v]. In addition, self-created audio-visual clips and memes form a large part of digital fandom demonstrated by the fans on these social networking sites. The Turkish fans also translate news reports related to IPKKND from YouTube channels like Tellytalk in Hindi/English to Turkish language and post it on their channels. To increase interactive engagement amongst the fan community, they also post multiple-choice questions related to the show and encourage user participation.

Although there are a plethora of images of the actors that are re-created through textual additions and visual imagery by the digital fans, the one illustrated below (Fig 1.2) demonstrates how the Turkish fans eliminate the Indian/Hindu identity of the character Khushi and reappropriate the actress as a Muslim (Turkish) woman in hijab. This recreated image further complicates the reel/real dichotomy of Irani’s stardom by introducing her fans to a new digital identity which marks a shift from both the character Khushi and the actor Irani. Another image (Fig 2.1) is recreated by using the images of Khushi and Arnab and superimposing it with a crescent moon and text to wish ‘Ramadan Mubarak’ to the Turkish fan community, thus omitting the original signification of the image and replacing it with new signifiers. Both these images illustrate that although transnational stardom offers multiple opportunities and global fame to the star, it also complicates the star-image in a trans-cultural context. In a globally changing media environment where the deterritorialized body of the star finds new significations in a trans-cultural, transmedial and transnational mediascape, the discourse on stardom also calls for new scholarly interventions.

Fig 2.1 A photoshopped image of Khushi and Arnab posted on a Facebook fan page to wish Ramadan Mubarak

Global TV meets Local Fans: The case of Hybridised Fan-texts

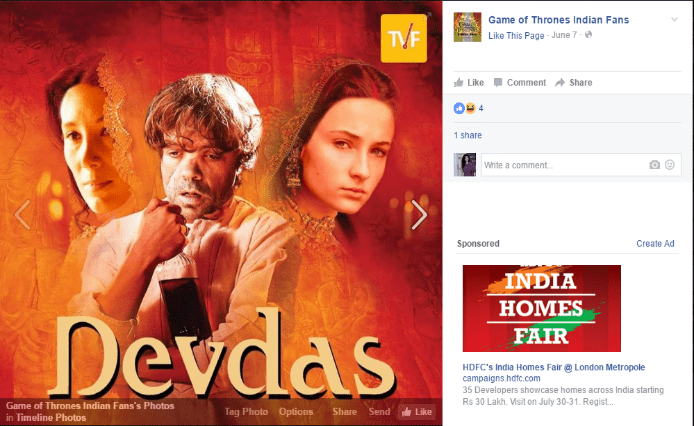

When the rumours of an Indian remake Rani Mahal of the globally popular American TV series Game of Thrones to be produced by Ekta Kapoor came out last year, within no time social networking sites were flooded with memes and GIFs that ranged from being informative to satirical. While a section of the Indian fan community demonstrated their angst by posting satirical memes and GIFs, the other section was constructively involved in suggesting star cast, storylines and dialogues for the Indian version. With a heavy inflow of foreign televisual content in the Indian market, through both formal and informal channels, Indian audiences are not only engaged in consuming but also re-appropriating international content with Indian sub-text. Similar to the IPKKND phenomenon in Turkey, Indian fans of international television content also find new appropriations of popular TV series like F.R.I.E.N.D.S., House of Cards, Game of Thrones etc. in a transcultural context. Posting/Sharing images of American TV actors in Indian avatar, suggesting Indian titles/star-cast for American/British TV series, making desi spoofs of English TV series or adding Indian sub-text to international content via text/images/audio are some common ways through which Indian fan community engages with International content on social networking sites. Where on the one hand, individual fans indulge in creating amateur fan-text in the form of memes, GIFs etc;, on the other, producers of digital content like The Viral Fever (TVF), Tales N’ Talkies etc. have also invested in creating good quality entertainment in the form of spoofs, mash-ups etc. and have added to the digital fandom of global television in India.

Fig 3.1 Screenshot of an image shared on the Game of Thrones India fan page that re-appropriates Game of Thrones characters in the Bollywood classic Devdas.

Fig 3.1 Screenshot of an image shared on the Game of Thrones India fan page that re-appropriates Game of Thrones characters in the Bollywood classic Devdas.

Fig 3.2 A Bhojpuri spoof of the American TV series The Big Bang Theory.

Fig 3.2 A Bhojpuri spoof of the American TV series The Big Bang Theory.

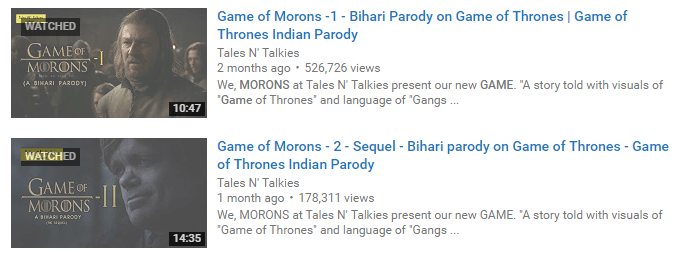

From musical rendition of the original sound track of Game of Thrones in Carnatic music to a Hindi theme song of the series, the series has a huge fan-base and an abundance of cultural re-appropriation when discussing its digital fandom in India. More recently, a Bihari parody of the series titled Game of Morons that claimed to tell a story “with visuals of Game of Thrones and language of Gangs of Wasseypur” released by a YouTube channel Tales N’ Talkies went viral on social networking sites. Released at the time when the sixth season of the original version was on air, this parody received an overwhelming response with two episodes released so far. With a storyline similar to the original series, Game of Morons is re-contextualized for the Indian audiences by using dialogues dubbed in Bhojpuri, characters acquiring Hindi names, fleeting cultural references and usage of Hindi idioms and slangs. The hybridised product (Game of Morons) thus produced, demonstrates an interesting yet complex global-local interface. This interaction between the global and the local form gives way to a new transcultural product that dislodges the content from its original context and re-contextualizes it to become meaningful for a particular set of audiences. Furthermore, to make meaning of the signifiers that produce such transcultural by-products, prior knowledge of both the original text and the cultural re-appropriation conferred to it also appears as a precondition in the consumption of such hybridised fan-texts.

Fig 4.1 Screenshot of Game of Morons parody shared on YouTube.

Fig 4.1 Screenshot of Game of Morons parody shared on YouTube.

Digital Fandom and the discourse of Fan Labour:

Digital fans occupy ‘virtual spaces’ to interact with one another and their stars and in such orders of communication produce cultural products that engage not just a particular fan community but also others outside of it. By producing audio-visual material, writing fan-fiction and fan-theories, providing subtitles to foreign content etc. fans, as Mark Andrejevic notes, provide labour that is “readily accessible to the mainstream- and to the producers themselves”[vi]. This form of fan labour also provides free promotions of the televisual text and the star in the digital domain. However, a re-categorization of both fan labour and fan-text would be helpful in understanding if comments, shares, re-tweets must also be considered as fan-texts and thus constitute as fan labour when compared to a well-maintained blog or a professionally created audio-visual spoof? While there is free and wilful labour provided by amateur individuals, there is also paid and skilled fan labour that interests professional producers and expands new media economies. How then must digital fandom as labour be constituted into one homogenised category? Also, in a transnational and transcultural context, digital fandom provides incredible possibilities for televisual texts to interact with local popular cultures. While transnational fandom can be understood within the rubric of globalization and transnational circulation of media content, why a particular televisual text gains prominence over other texts and attracts digital fandom in a transcultural context is a query that requires further exploration.

Notes:

[i] Holmes, Su and Sean Redmond. “Introduction: Understanding Celebrity Culture.” In Framing Celebrity: New Directions in Celebrity Culture, edited by Su Holmes and Sean Redmond, 1-16. New York: Routledge, 2006.

[ii] Srinivas, S.V. “Devotion and Defiance in Fan Activity.” Journal of Arts and Ideas, 1996: 1- 17.

[iii] Shanti – Ek Aurat Ki Kahani was the first Indian daily soap opera that was telecast on Doordarshan in 1994. The lead character Shanti was played by the popular model cum actress Mandira Bedi.

[iv] IPKKND has been dubbed in regional languages like Malayalam as Mounam Sammadham, Telugu as Chuppulu Kalisina Shubhavela and Tamil as Idhu Kadhala. It has also been adapted in Bengali as Bojhena Se Bojhena, Arabic as Men Nazra Thanya and Vietnamese as Moi Tinh Ki La.

[v] For instance, on Sanaya Irani’s fan page Sanaya Irani Fan Turkiye, one can witness clips from her fiction show Rangrasiya and reality show Jhalak Dikhla Ja.

[vi] Andrejevic, M. (2008, January). Watching Television Without Pity: The Productivity of Online Fans. Television & New Media, 24-46.