This is the third research note by Ritika Pant, one of the researchers who received the Social Media Research grant for 2016.

In 1974, when Raymond Williams was formulating the concept of “flows” in television broadcasting, he thought of them as “the defining characteristic of broadcasting, simultaneously as technology and as a cultural form” (80)[i]. Dismissing the notion of commercials as “interruptions” in between televisual content, he was, instead, mesmerized by the seamless “flow” of American TV that weaved in programmes and advertisements into a rhythmic structure. Speaking of broadcast TV, John Ellis emphasized the significance of “flow” through “segmentation” and considered it as a distinctive aesthetic form of TV programming[ii]. Instead of a single coherent text that cinema offered, Ellis observed, that television programming was formed of “small sequential unities of images and sounds” that flowed with the logic of sequence or repetition (1982:112).

Since televisual content in the digital age is typically devoid of interruptive commercial breaks and often viewed as a cinematic whole, William Uricchio’s conception of digital flows seems more appropriate to discuss the post-network television flows. From programme-centred flows that were governed by the broadcasters, Uricchio suggests that digital technologies and remote-control options have introduced us to a new set of flows governed by “choices and actions initiated by the viewer” (Uricchio, 2004: 170)[iii]. While the advancement in digital technologies must be applauded for this shift, televisual content that is constantly innovating itself to keep up with the digital explosion must also be paid its due. In this post, I examine the transformation of television content for online consumption and discover new aesthetic regimes created by the transfusion of the televisual with the digital.

Televisual Content, Digital Audiences:

As discussed in the previous post, the mushrooming of OTT services in India has expanded the distribution circuits of television content and has provided alternate methods of watching the same content through mobile phones, laptops etc. The users indulge in either downloading content off the internet, mostly through pirate circuits like torrent, or viewing it through online streaming services. Both the patterns of viewership provide diverse user experiences. Moreover, online televisual content may be broadly divided into two categories – content that is specifically transmuted for the digital users and content that is “as is” provided through OTT platforms[iv]. The content “as is” provided for online consumption does not undergo major transformations aesthetically, the main difference, however, is felt experientially that I shall discuss later in the post.

For now, I will closely examine the first category with reference to the television network Viacom 18’s newly launched mobile app and desktop version, Voot to examine how television programming is “made easy” for access to the digital users[v]. While I specifically explore the Voot app, most of its features may hold true for other OTT services as well. Launched in March 2016, Voot is the latest ‘advertising-led-VOD platform’ in the Hindi General Entertainment space. The content from different genres across Viacom 18’s TV channels is arranged in one app under tabs named Comedy, Drama, Reality, Voot Kids etc. To promote individualized content, a search bar on the top of the page allows the users to search specific content they wish to watch. Additionally, a tab ‘Vooting Now’ highlights trending episodes of latest shows and recommended movies. A search of the popular soap opera Balika Vadhu, for instance, brings the users to the home page of the show that displays a list of episodes starting from the most recent ones. While full length episodes of approximately 19-20 minutes duration are available on the app, it also allows for bonus content in the form of mini clips or ‘Voot Shorts’ containing 3-5 minutes clips of specific scenes with a brief textual description of an episode or a scene. Unlike television audiences who cannot zap through specific sequences or commercials during broadcast, digital users have an added advantage of watching and re-watching selective episodes and specific scenes from those episodes if they so desire. The same video clip can also be shared on social networking sites. An additional feature that of ‘shout’ allows the users to voice their opinion and react to the content they have just watched. Although commercials are not included as of now and do not cause interruptions in-between the programming, but promos of various TV shows appear at the beginning of each episode. The app also enables the users to create a personal profile that monitors their preferences and tracks their viewing history. Where on the one hand, users get customized content by registering themselves on apps like Voot; from the broadcaster’s perspective, such digital initiatives obliterate the anonymous universe of the audiences where they are not registered as mere numbers to record the TRPs of a channel. Instead, such user profiling helps the broadcasters define their universe, track the viewership patterns of their audiences and thus offer content as per their (audience) interests.

Fig 1.1 – A list of short episodic clips specifically designed for web audiences in the Voot app. Source: www.voot.com

Fig 1.1 – A list of short episodic clips specifically designed for web audiences in the Voot app. Source: www.voot.com

Fig 1.2 – The feature of ‘shout’ allows users to register their reaction to the content in these ways. Source: www.voot.com

The ‘New’ Televisual Aesthetics:

Whereas television is purportedly consumed in a distracted state mostly in a living room environment, watching a TV series on a laptop or a smartphone screen with headphones on, devoid of other living room commotion, provides for an immersive user experience. While the downsizing of the screen may help in better quality resolution, a relatively closer distance between the user and the screen helps register the minutest of on-screen details[vi]. Also, the affective charge that such proximity between the user and the screen/text produces could be varied depending on both the proximity and the text. While one may consider such isolated viewing as exempted from surrounding distractions, the user’s attention, however, may shift from one window to another often resulting in multi-tasking. This multi-tasking leads to what Will Brooker terms as an “overflow” experience, wherein users pause the ongoing series and start exploring extra-textual material on the internet that could include extricating information about the show, joining live chats with the fan community of the show, discussing it through blogs or even sharing it on social media[vii]. Along with asynchronous viewing, such viewership provides viewers with “multiple opportunities to engage with a particular piece of content”[viii]. This is clearly evident in the Voot example that I discuss above.

The digital medium exceeds the passivity of a television viewer and calls for an active engagement by continuously offering more content through related links, sharing and commenting on the content. Also, watching a TV show online and then following a series of links that are recommended on one’s viewing habits often help the viewers to contextualize, re-contextualize and de-contextualize the content and provide newer significations to the same content in each viewing. This active involvement with the text paves the way for new kinds of flows that are more user-oriented. Therefore, I suggest that while digital technologies have created a new set of flows that are viewer-oriented, televisual content that is so designed as to support a friendly user-interface also plays an important role in the new age digital flows.

Television content, when consumed via the online/digital medium, transmutes televisual aesthetics and produces a new kind of aural-visual experience specific to contemporary convergence culture. For example, the concept of “coming-up” graphic window that highlights the content of the next segment before going in for a commercial break which broadcasters utilize to engage their viewers to resume to the same show after the break, seems to have eliminated in the digital space. Since there are barely any interruptions in between the show and the entire episode is viewed not in segments but as a cinematic whole, “coming-ups” no longer find space in the programming content for the digital users. Online televisual content has also compromised with the televisual aesthetics of segmented-structure typical to any kind of television programming, where each segment is expected to have a character, conflict and resolution. This gains prominence in downloaded content wherein not just the segmented-structure but also the episodic nature of a televisual text is reduced to make a television series feel like a never ending cinematic experience, at least for binge-watchers. As a result, cliffhangers which were essentially an important element of a soap opera, now, find little emphasis in the soap-opera format. Since they are a crucial story-telling element and also an audience-puller, they instead find place in the last episode of a particular season of a TV series, so that the audiences/users are glued to the next season[ix].

Censorship and Televisual Content:

Fig 2.1- A screenshot of an article published on Waqt Ne Kiya Kya Haseen Sitam

Source : www.hindustantimes.com

Fig 2.2 – A screenshot of discussion about Waqt Ne Kiya…among two users on Quora

Fig 2.2 – A screenshot of discussion about Waqt Ne Kiya…among two users on Quora

Unlike films, Indian television does not necessitate a censor board certificate to broadcast its content. However, in order to avoid offensive content, television follows a set of self-regulatory guidelines prepared in 2011 by the Indian Broadcasters Federation. Every broadcaster has a Standards & Practices (S&P) department in place that reviews all the content before its telecast. With Indian audiences giving overwhelming response to foreign content, the self-censorship practice of Indian TV channels has become more ridiculous than restrictive[x]. Beeping words and editing scenes which are gory, sexually explicit or religiously offensive often results in an episode with missing plots in the storyline. Online streaming platforms and illegal torrent downloads become the only resort for irate television audiences who fail to make sense of abrupt narratives with ruthlessly edited televisual content.

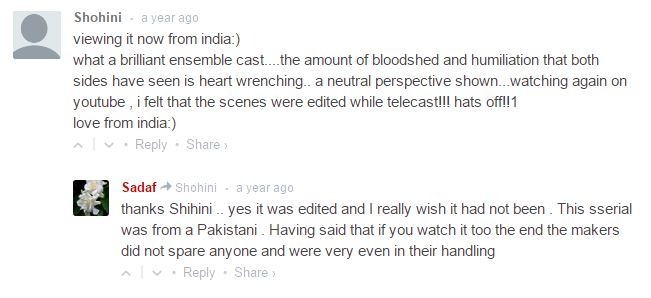

Not just English content but also Bollywood films and Pakistani soaps are illogically edited to avoid censorship issues on television. Apart from the example of Waqt Ne Kiya Kya Haseen Sitam that I mentioned in my first post, other Pakistani shows like Mann Ke Moti and Ishq Junoon Deewangi have also had edited versions being telecast on Indian TV with titles changed to Khel Qismat Ka and Ijjazat respectively. In a telephonic conversation with Shailaja Kejriwal, Chief Creative Head of the entertainment channel Zindagi, she mentions “Although such changes are totally uncalled for but we have to keep in mind that there is a large section of audiences who are watching these shows on YouTube and not television” [xi]. Changing the titles of the series decreases the possibility of searching a TV series or an episode on Youtube and as a result the audiences return to the TV sets. The digital domain, not only provides for uncensored text but also provides extratextual material that results in contextualization, re-contextualization and de-contextualization of televisual content via broadband as opposed to broadcast. Concluding this post with the example of Waqt Ne Kiya…it maybe suggested that the YouTube version of the show goes beyond a regular television broadcast and manages to produce personal accounts of oral histories of India-Pakistan partition. The discussions often deviate from the actual text to many inter-related issues, like the one illustrated in Fig 3.1. While a television broadcast may claim to offer firsthand content to its audiences, online televisual flows generate para-texts that a television broadcast may only dream of.

Fig 3.1 A screen-shot of the comments section of the series Dastaan (Waqt ne Kiya..) on YouTube.

Notes:

[i] Williams, Raymond. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. London : Fontana, 1974.

[ii] Ellis, John. Visible Fictions: Cinema:Television:Video. USA, Canada: Routledge, 1982.

[iii] Uricchio, William. “Television’s Next Generation: Technology/ Interface Culture/ Flow.” In Television after TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition, edited by Lynn Spigel and Jan Olsson, 163-172. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004.

[iv] Another category of content available for digital users is Webseries (original programming produced only for the digital domain like TVF Permanent Roomates, Pitchers, Love Bytes etc). In this post, however, I specifically look at translation of televisual content for digital domains – content that was produced for television and later made available for digital users.

[v] Voot also has a desktop version for web users with the url www.voot.com.

[vi] This is not to generalize that all kinds of content may be enjoyed in an isolated viewing like this. For example, a cricket match, or news, that has a liveness factor to it, may still be enjoyed on a bigger TV screen in a living room set up.

[vii] See http://web.mit.edu/uricchio/Public/television/brooker%20online%20viewing.pdf . A user could, perhaps, also be distracted by surfing/watching something completely irrelevant to the content that he was earlier watching. This competition between several equally demanding screens is what Will Brooker defines as “interflow”.

[viii] Extracted from a research paper titled “Understanding Television as a Social Experience”. http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/mit7/papers/Frigo_MIT-MEL_SocialTV.pdf

[ix] Although there could be many examples to substantiate this, but one of the most discussed cliffhangers of the recent times was in the Season 5 of the TV series Game of Thrones which ends with the supposed death of one the most popular characters Jon Snow. The audiences were eagerly awaiting Season 6 with much anticipation regarding the same.

[x] The irrational editing techniques of the Indian TV channels to refrain from censorship issues are explained in this light-hearted satirical video. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ro25-o-DWCw .

[xi] The interview with Shailaja Kejriwal was taken via telephone on October 4, 2015.