This is the second research note by Ritika Pant, one of the researchers who received the Social Media Research grant for 2016.

In a stylistically treated advertisement of the Indian Premiere League (IPL) 2016, a group of youngsters in various environments like that of an office, college and home are hooked to their smartphones for latest cricket updates. The advertisement ends with the tagline “screen chhota hai toh kya hua, dil bada hai yaar” (what if the screen is small, we have a big heart). Furthermore, the tagline of IPL 2016 on hotstar is “jab jab cricket, tab tab hotstar” (Think cricket, Think hotstar). This commercial, that attempts to dismantle the television-cricket relationship and draws an association between cricket and hotstar, indicates the emergence of a post-network era wherein television content, not just cricket, but soap operas, movies and even news no longer remain limited to the small-screen but dominate the ever-expansive digital universe[i].

Thanks to the proliferation of digital technologies, especially smartphones; and penetration of the internet, television content is now distributed through over-the-top (OTT)[ii] platforms and is available anywhere, anytime on any device. This post navigates the circuits of distribution of television content via broadband services through OTT platforms like hotstar, Netflix etc. and examines how online streaming services are altering traditional television content distribution practices and thereby creating new televisual experiences for the Indian audiences. Although it would be interesting to note how various genres like sports, news etc. responds to these mutations but for the purpose of this post, I limit my analysis to the entertainment genre.

Network to Post-network Televisual Transition

In The Television will be Revolutionized (2007), Amanda Lotz discusses the three stages of television broadcasting – the network era, the multi-channel transition and the post-network era[iii]. The network era, Lotz suggests, had a limited number of broadcasting networks having maximum control with the broadcasters, the multi-channel transition observed a splurge of content that came through satellite television and Cable TV along with viewer-controlled technologies like the Video Home System (VHS) and the remote control. The post-network era shifts the control completely from broadcasters to the audiences and is thus characterized by the consumption of television content where “control technologies have effectively added to viewers’ choice in experiencing television” (29). It marks a break from linear content to “prized content” – “what is on” television to “programming that people seek out and specifically desire” (ibid :12).

In India, the arrival of video in the 1980s altered the concept of linear content and the temporality of television consumption as it allowed for time-shifted viewing of television content. But living rooms and television sets as material objects remained integral to televisual experiences even during the multi-channel transition. The post-network era, however, has transformed these experiences as television content no more remains restricted to the small-screen and is consumed in mobile environments. The primal cause for this may be traced to the newer ways of distributing televisual content that the broadcasters have adopted. While satellite broadcasting still remains dominant in India, distribution via broadband services is gradually gaining momentum[iv].

With the third largest internet user-base in the world after China and the United States, internet has reached almost 35% of the Indian population. The Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI) report (February 2016) suggests that by the end of June 2016 India will have almost 371 million mobile internet users, including 109 million rural populations. It is assumed that this surge has been possible due to the increase in the supply of low-cost Chinese manufacturing smartphones like CoolPad, Xiaomi etc. in the Indian telecom market. Moreover, mobile networks’ reduced data plans and a speedy transition from 2G and 3G to 4G networks, have also encouraged mobile users to avail internet, specifically video content, via their handsets[v]. In such a scenario, the future of mobile entertainment in India appears promising.

Source: www.dazeinfo.com

Mapping the Over-the-top services of Television Distribution in India:

Star India Pvt. Ltd’s digital and mobile entertainment platform, hotstar, launched alongside ICC Cricket World Cup in February 2015 has taken the Indian digital mediascape by surprise. Primarily developed for mobile users, the app that also has a desktop version for web users provides broadcast quality entertainment to viewers at an internet bandwidth of as low as 50kbps. Over 50,000 hours of television content in the form of drama, movies and sports from all of Star network’s popular channels like Star Plus, Life OK, Star World etc. is provided on one platform after 24 hours of its original telecast. The mobile app also offers different genres of entertainment in many regional language channels like Maa (Telugu) and Star Pravah (Marathi) as well. Alongside, hotstar is also invested in producing original content like On Air with AIB[vi] specifically for the digital audiences. For an efficient user-interface, the content is further classified into genres, programmes, specific episodes and short video clips making the content easily accessible for smartphone users. While the content in Hindi and regional languages catalogue is subscription-free, premium content on HBO Originals that offers latest international TV series and selective content on Star World do require a subscription fee[vii]. With the launch of the sixth season of the globally popular TV series Game of Thrones (GoT), hotstar, for the first time announced paywall at Rs.199 per month for its premium content. More importantly, while the television audiences in India have to wait for 36 hours to watch the latest GoT episode, that too with censored content, hotstar users can watch uncensored episodes minutes after its US telecasts. Given that GoT tops the list of most pirated shows globally, such a move may curtail online piracy to some extent and restrict users from downloading good quality torrent links.

Having realized the potential of OTT platforms, most of the leading Hindi Entertainment channels have entered the digital universe of online streaming. Zee TV’s DittoTv and Ozee, Sony Entertainment’s SonyLiv and lately Viacom 18’s Voot websites and apps are the digital counterparts of their host channels. Before the emergence of these OTT platforms, most of the channels’ content was uploaded on their respective YouTube channels where users could watch full length episodes of their favourite shows. But now, with the proliferation of OTTs, YouTube channels only serve as platforms to promote the channels’ content and redirect the online traffic to their respective OTTs[viii]. Not withholding the digital rights of English entertainment, these platforms, however, lack international television content, unlike hotstar.

Screenshot of a YouTube search on the episodes of TV soap Dahleez directs the users to the hotstar app. Source: www.youtube.com

As a major competition to this, and to fill the void that Hindi General Entertainment OTTs have created, independent video streaming services like Pritish Nandy Communictation’s Ogle, Singapore-based Singtel’s HOOQ and Singapore-based Spuul have played a pivotal role in bringing both Indian and international content to the users[ix]. Most of these platforms offer ad-free content at low bandwidths on multiple devices, which can either be streamed online or watched offline at a later time. For example, HOOQ while on the one hand, evokes nostalgia with a classic collection of Indian television shows of the late 80s and 90s like Ye Jo Hai Zindagi, Nukkad and Fauji, it also has latest American TV series like Fringe and Chosen. An assortment of English, Hindi and regional television content and films, these services offer their users à la carte programming completely based on viewers’ preferences as opposed to the earlier practice of Cable television bundling[x].

Screenshot of Ogle’s Homepage promoting ad-free content. Source – http://ogle.rocks/index.html#about

The launch of Netflix, world’s premier online video streaming service, in January 2016, was expected to bring a major breakthrough amongst OTT services in India. With a subscription fee of Rs.500 for its standard definition services and only 7% content from its global catalogue, Netflix India users already feel disgruntled[xi]. Moreover, Hindi television shows are a major deficit in its catalogue. The service is now seeking Pakistani soaps like Humsafar etc. because firstly, they are cheaper in acquisition when compared to Hindi soaps and secondly, Hindi TV broadcasters are already providing their content via their own OTT platforms. Moreover, taking into account the fair usage policy limits, an average user may not be able to watch enough content online[xii]. Furthermore, by blocking access to most of its global content for the Indian users, Netflix defeats its purpose of fighting online piracy in India.

Transforming the Televisual in the Digital Era

With the post-network television transitioning from a broadcast medium to a narrowcast one, televisual experiences of the audiences have also transformed radically. While the Cable TV bundle is gradually becoming obsolete, the users are choosing pay-as-you-pick options by streamlining the programming that interests them. Online users take pleasure in watching individualized content and binging on it as opposed to television audiences engaged in community viewing and periodically waiting for the next episode’s telecast[xiii]. This furthers the possibility of audience fragmentation as dedicated screen-time to a TV set is resulting in shared-screen time to multiple screens in the post-network era.

Apart from providing time-shifted viewing of content on alternate screens, online distribution of televisual content also compels us to reconsider the ways in which the concept of television channels, genres or even primetime is transforming. When multilingual content in multiple genres is available to the users or rather “viewsers”[xiv] as Dan Harries suggests the term, on one platform, how does one perceive of sports, lifestyle and entertainment channels as distinct categories? How must TV producers create content for daytime audiences that also serve the need of prime-time audiences? When the users are watching televisual content on multiple devices, must then, television, be considered only a delivery technology amongst other technologies?

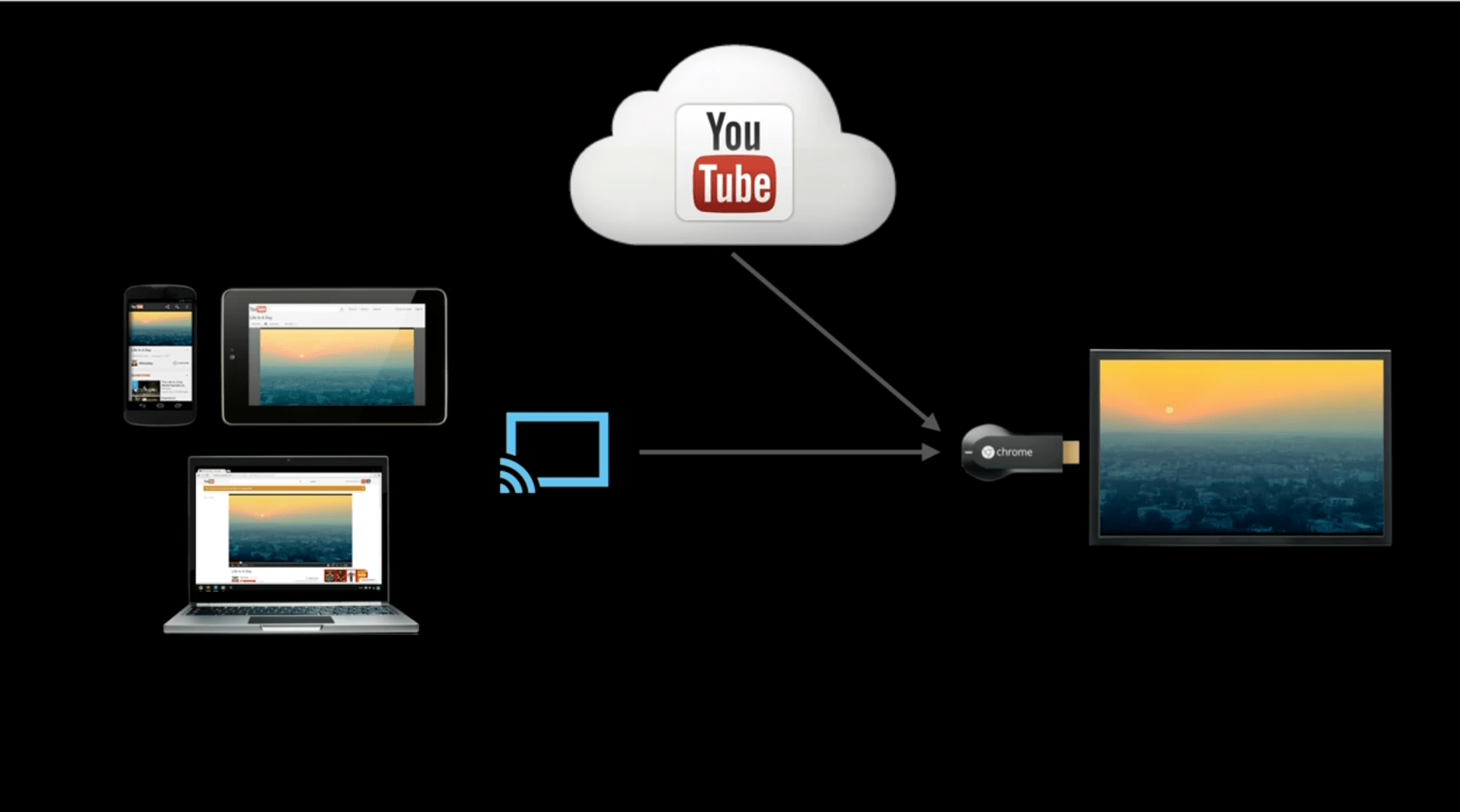

An image depicting the functioning of the media streaming device Google Chromecast

The latest addition to the digital landscape of televisual innovations is the launch of Google Chromecast in India this April. Chromecast is a dongle-like media streaming device that is plugged into the HDMI port of a HD television. With a Wi-Fi connection, it allows the users to stream online videos via their smartphones or laptops and cast onto their television screens. While one may watch the same content on their smartphones or laptops, the basic function of Chromecast is to watch this content on a bigger screen. Where on the one hand, OTT platforms encourage users to watch televisual content via internet onto other devices; Chromecast, by streaming content off the internet brings the users back to the TV screen. The distribution methods may vary with the enhancement of technology but with such innovations, TV sets as material objects, as technological devices or as cultural artifacts will remain an integral part of our living rooms.

Notes:

[i] It is also interesting to note that the sponsor of the current season of IPL is a China based smartphone company – Vivo. Hotstar, which is the official digital streaming partner of Vivo IPL 2016, is thus promoting its viewers to watch IPL only on hotstar thereby doing an indirect promotion for VIVO. Prior to this, IPL was sponsored by the real estate developer DLF and Pepsico

[ii] Over-the-top platforms deliver audio-visual content over the internet without involving Cable Operators and satellite broadcasting.

[iii] Lotz, Amanda D. The Television Will be Revolutionized. New York and London: New York University Press, 2007.

[iv] In fact, Direct-to-Home satellite services are also venturing into distributing video-on-demand services via broadband. For example, Airtel Digital TV offers On Demand TV through the Internet and its Pocket TV is a mobile app which allows customers to watch TV on the move.

[v] Interestingly, the usage of mobile data for entertainment (esp. video content) is much higher in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities as compared to metropolitans.

[vi] On Air with AIB is a topical show that adds humour to the issues of current interest. It has often been criticized for its uncensored content and the use of sexual innuendos. One of the episodes of the show received extreme criticism and was removed from YouTube as the content was deemed inappropriate for the audiences.

[vii] HBO Originals offers popular series like True Detective, Sillicon Valley and Vinyl to the hotstar users.

[viii] The YouTube channels of the Hindi Entertainment broadcasters now upload 2 to 3 minutes content that functions as a teaser to redirect the audiences to their respective OTT platforms.

[ix] Eros Now, BigFlix, BoxTV and YuppTV are some other OTT players in India.

[x]Cable TV works with the concept of bundling where a few channels are bundled together into a pack. This often combines channels of high interest with channels of low interest. The consumer who opts for a bundle cannot pick channels as per choice but has to pay for the entire bundle whether he/she watches it or not. In this the consumer does not have the option to pay-as-you-pick a channel. This has been the major distribution method ever since Cable TV arrived in India.

[xi] Netflix Original’s House of Cards was also added much later, in March, to the Indian catalogue.

[xii] Under Fair Usage Policy, the data transfer limits of the plan remain same; however, after reaching a certain limit of data usage, the internet speed reduces considerably. By putting a bandwidth cap on the internet usage (even in an unlimited data plan), the broadband service allows for a fair share of internet bandwidth for all the users. Netflix’s website recommends that a minimum of 5 Mbps data speed is required to watch a HD quality video which will consume almost 3 GB data an hour.

[xiii] The mobile app hotstar’s tagline “Go Solo” also suggests that television viewing is no more enjoyed as a simultaneous viewing experience since choices of televisual content differ from individual to individual and that post-network television allows for such varied user experiences. See the advertisement https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iayQnNuctgo

[xiv] See: Harries, Dan. The New Media Book. London: British Film Institute, 2002. Dan Harries defines “viewsers” as the new “connected consumers” and “viewsing” as “the experience of media in a manner that effectively integrates the activities of both using and viewing” (17).